RIVAR Vol. 5, N° 14. Mayo 2018: 39-60.

Artículos

Between Localness and Deterritorialization in Nemea and Basto Wine Regions

Entre localidad y desterritorialización en las regiones vitivinícolas de Nemea y Basto

José Duarte Ribeiro*

Elisabete Figueiredo **

Carlos Rodrigues ***

*Currently enrolled in a Doctorate programme in Sociology at Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey where is developing a research on Turkish wine regions within the context of European Union accession process and its agricultural adjustments in Turkey. Email: jose.ribeiro@metu.edu.tr.

**Assistant Professor of Department of Political, Social and Territorial Sciences & Member of the GOVCOPP (Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policy Research Unit) at University of Aveiro. Email: elisa@ua.pt.

***Head of Department Social, Political and Territorial Sciences & Member of the GOVCOPP (Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policy Research Unit) at University of Aveiro. Email: cjose@ua.pt

Resumen

Entre el conocimiento y las dinámicas de negociación de poderes de todos los actores implicados (desde los viticultores hasta los agricultores, autoridades locales y otras partes interesadas como las cooperativas locales) existe una necesidad de cuestionar si las estrategias de desarrollo rural actuales, basadas en las estrategias de calificación de producción de alimentos locales bajo las Indicaciones Geográficas (IGs), están siendo implementadas hacia el desarrollo extensivo de la región, su comunidad local y, por consiguiente, a la protección completa del terroir vinícola en un sentido más amplio que únicamente el de origen y calidad. Esta necesidad de cuestionar viene acompañada de un reciente y renovado interés por la noción de terroir, donde surgen debates sobre la preservación/recreación del terroir en el proceso continuo de la historia y también la discusión de la extensión de la capacidad de las IGs para proteger el terroir como historia, legado o patrimonio.

Nemea (Grecia) y Basto (región de Vinho Verde, Portugal) son dos regiones vinícolas de alta calidad bajo la protección de denominaciones de origen que tienen, por lo general, el formato de IGs. Recientemente, han surgido debates sobre la reconstrucción del conocimiento local/tradicional y, en consecuencia, en la reconstrucción de los terroirs de ambas regiones, generando desafíos para el desarrollo de las regiones entre la preservación del carácter local (implícito en las Denominaciones de Origen) y las amenazas de la desterritorialización.

Palabras clave: terroir, Indicaciones Geográficas, alimentos locales y desarrollo rural, localidad y desterritorialización.

Abstract

Between the knowledge and power negotiation dynamics of all the actors involved (from winemakers to farmers, local authorities and other stakeholders like local cooperatives) there is a need to question if the current rural development strategies based on local food qualification schemes under Geographical Indications (GIs) are being implemented towards the extended development of the region, the local community and therefore to the full protection of wine terroir on a broader sense than only origin and quality. This comes along with recent renewed interest on the notion of terroir, where discussions emerged about the preservation/re-creation of terroir on the ongoing process of history and the discussion on the extent of GIs capacity to protect terroir as history, heritage or “patrimoine.”4Nemea (Greece) and Basto (Vinho Verde region, Portugal) are two high quality wines regions under the protection of labels of origin commonly under the framework of GIs. Recent discussions have emerged on the re-construction of local/traditional knowledge and thus on the re-construction of both regions wine terroir, that are related with challenges to the development of the regions between the preservation of localness (implicit on the protection by labels of origin) and the threats of deterritorialization.

Keywords: Terroir, Geographical Indications, Local Food and Rural Development, localness and deterritorialisation.

“Pruning”

Local Food and Geographical Indications: considerations for Portuguese and Greek Cases

Official schemes in agro-food products qualification have a long history. If we consider the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), and also the Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), labels from the EEC Regulation 2081/92, they are based on protocols developed in the late 19th century, in France, to protect the uniqueness of wine regions like Bordeaux from fraud after the phylloxera epidemic situation that cause enormous damages in many wine regions in Europe.

Nowadays qualification systems are, at a great extent, based on this wine qualification system, which means that the entanglement between product and territory is explored in two different directions: first linking the wine to the local through the concept of terroir and second linking the wine to the global as geographical indication (Barham, 2002; Van Leeuwen and Seguin, 2006). In fact, wine terroir is one of the most recognizable expressions to represent the idea that qualified products characteristics are tied to physical and cultural specificities of a given territory - representing its uniqueness.

In sum, the qualification systems by which, supposedly, qualified producers distinguish themselves by following an accepted and regulated code of practice, rely on the premise that consumers are willing to pay a premium price because they value certain quality levels. However, one has to understand whether or not there is awareness on the consumer’s side concerning the localness of the product that, once again supposedly, qualification systems should protect.

Greek and Portuguese “rural world(s)” have been losing its (strictly) agro-productive character, going through an identity crisis (Figueiredo, 2008).

For the case of Portugal, several authors refer that, after this identity crisis, there has not yet been found answers that lead to a new agro-rural paradigm (Covas, 2011; Oliveira Baptista, 2011). For the case of Greece, three paths are identified as main responsible for changing the physiognomy of rural Greece in the last 20 years. They are “de-agriculturalization of the countryside, rural mobilities and rural resilience during economic crisis” (Kasimis and Papadopoulos, 2001; 2013). The same authors argue that this three processes (at certain extent similar also in Portugal) have transformed internally the rural areas, forming a new rurality: “[...] characterized by contraction of agriculture, expansion of tourism and construction, increased pluriactivity, increased employment of international migrant labour and the reorganization of farm family labour and operation” (Kasimis and Papadopoulos, 2013: 263).

Furthermore, both Portuguese and Greek agricultures are still mainly related to household farming, very traditional and small scaled (Louloudis and Maraveyas, 1997; Santos Varela (2007). In addition, another aspect that Portuguese and Greek rural areas are apparently similar to each other is the fact that both are spaces of consumption that stand out (albeit timidly) as an alternative to large commercial spaces and processes of globalization. Consequently, is undeniable the importance for both countries the connection between local food and alternative (localized) food systems (Kasimis and Papadopoulos, 2013; Ribeiro et al., 2014).

An interview (carried within the research context) with the Secretary General of Agricultural Policy & Management of European Funds in the Greek government, received the following answer to the question about the vulnerability of local producers in the current context of economic crisis:

If we try to have an agriculture sector that would compete with what we know has commodities agriculture production system then Greece will fail. Because of various reasons concerning structural problems like small size of holding, high parcelization, low productivity and that will not allow us to be competitive with large scale agricultures of England, Germany, and France. The comparative advantages of the Greek agriculture sector, in my opinion, is to make a shift from the conventional production model to a production model which will explore the comparative advantages resulting from the particular climatic conditions of this country in the production of products with identity, in other words, to quality products.

However, the investment on the qualification products faces a needed new approach that cannot only rely on the designation of origin per se, but rather an integration into a wider regional strategical plan, connected with other sectors of the economy and, more than anything else, to protect the most vulnerable groups in rural areas. Furthermore the involvement of the local authorities in the qualification is strongly needed, not only to reinforce the distribution of the added value for the sake of the local economies and to guarantee the communication between the interprofessional network and the local community, but also for the sake of the social development of the region.

Nevertheless, if in more localized markets, there is usually a higher recognition of origin products once there are closer connections between producers, retailers and consumers, this type of product have little market impact and thus local farmers face a high risk and vulnerability (Fonte, 2008; Fonte, M. and Papadopoulos, 2010). This way it is reasonable to question if European Union’s (EU) schemes are really needed or if they really make a difference. We do not advocate that European GIs have in itself a root of that failure, but for sure, they have to imply a stronger involvement of the local authorities that need to be empowered in order to stimulate sturdier rural governance networks at the local and regional level (Murdoch et al., 2000; Morgan, Marsden and Murdoch, 2006; Tregear et al., 2007).

The reinforcement of the politics of food systems, transversal to all actors involved (from farmers, producers, retailers, touristic agents, local authorities) while dissolving such power throughout the role of associativism seems to be the most effective (and democratic) to ensure that consumers are helped with information about the products uniqueness but also that farmers are encouraged to go for quality and the market operations are facilitated (while progressively increasing relocalization of consumption). However this reinforcement of the politics of food systems by conciliating various stakeholders and promote collective action is only possible if a more localized autonomy to manage the implementation of the origin qualification schemes follows along, simultaneously at the national and local levels. Otherwise inadequate legal establishments and rules from Brussels bureaucratic level will continue to constitute impediments to that referred reinforcement.

“Ripening”

Nemea and Basto wine regions: contextualizing the research problem

Nemea wine region is one of the biggest wine appellations in Greece, and one the two most important red wine appellation in the country. Nemea wine appellation coincides, almost totally, in terms of its demarcated area to Nemea Municipality.5 Nemea Municipality is located in the Prefecture of Corinth in the north-eastern Peloponnese. The Peloponnese must surely have been one of the first places on earth to systematically grow grapes and make wine (at least for the past 4,000 years). Corinth is the major red wine supplier of Greece, with a total vineyard hectares of 6,137 in which about a third (2,123ha) is Nemea VQPRD (Vins de Qualité Produits dans des Régions Déterminées).6 Nemea wine is the only PDO of the region and in fact, viticulture is the main agricultural activity in Nemea, where most local income comes from the wine economy. Considering its size as a wine region, Nemea is one of the major ones in the country, consisting of 17 rural communities and Nemea VQPRD is traditionally 100% Agiorgitiko grape variety.7 In Greece this wine appellation became registered in 1971, long before the implementation of the regulation of wine appellations by EU throughout the European Council Regulation 2081/92. This way Nemea wine has managed to go out from the anonymity as the historical place named Nemea began to appear on the labels of bottled wine. Actually, as expressed by Kourakou-Dragona (2012, pp. 137-148) it took 15-20 years for Nemea wine to go from anonymity to be marketed in bottles with the locality label, likewise it is very surprising that 40 years ago there was only one winery in the region while today there are around 34 wineries, of which 31 have Nemea PDO wines. The oldest and largest winery in the area is the Nemea Wine Cooperative that dates back to 1930’s, absorbing more than 50 per cent of the local production. It has around 1,700 members registered but our field visit to the Cooperative (mainly a tour visit without an interview)8 proved that only a bit more than a thousand keeps a regular activity as members. The members are vinegrowers that sell their grape production to the cooperative but they are also allowed and to sell their grapes to private wineries.

Figure 1. Greece and Nemea wine region

Therefore, although there is a millenary history of vine-growing and winemaking in this part of the vast Peloponnese, the evolution of Nemea as a high quality demarcated wine region was astonishingly fast as a “revolution” (term used over and over again by some of the winemakers interviewed). Furthermore, along this (r)evolution other processes took place as the viticulture practices employed for many years by the local vine-growers have been gradually replaced by modern, cutting-edge, internationally-influenced viticulture practices. Therefore the new system supports fewer vines per hectare but vine-grapes have more space to grow while the amount produced is way less, however targeting for higher quality grapes (Lazarakis, 2005). Nonetheless, a considerable number of farmers do not follow the modern practices, and so the winemakers9 that want to ensure high quality Agiorgitiko have established networks of trust with the farmers that follow viticulture practices intended by those winemakers. The networks of trust are important as some winemakers and other stakeholders underlined their role to stimulate and consolidate Nemea as a wine appellation, knowing that counter-acting processes of distrust may have the exact opposite effect.

A characterization under four-kind typology has been made by Papadopoulos (2010) (see below). Also important to state that our field research pointed that some slight differences have occurred since 2010 but they are not significant enough to make this typology overruled:

1. Do not bottle wine and sell bulk wine through informal networks or under subcontracting for outside companies (up to 7,000 hl).

2. Mainly producing for domestic market. Informal networks to sell and also work with large store receiving a percentage (less than 1,000 hl).

3. More dynamic in advertising and promoting their quality wine for export (1,000 -

4.000 hl).

4. Wineries of large capacity that sell wine to large Greek wine companies (7,000 -

100.000 hl).

Additionally, in terms of institutional relations one of the changes from 2010 to 2015 is the non-participation of the local Wine Cooperative in the interprofessional association of winemakers called SON created in 2011 after the previous ENOAN10 had closed. This has particular negative effects for farmers as their position remains the most vulnerable one in the network since they are the ones that have less felt and profited, directly and indirectly, from the rural development of Nemea wine appellation.

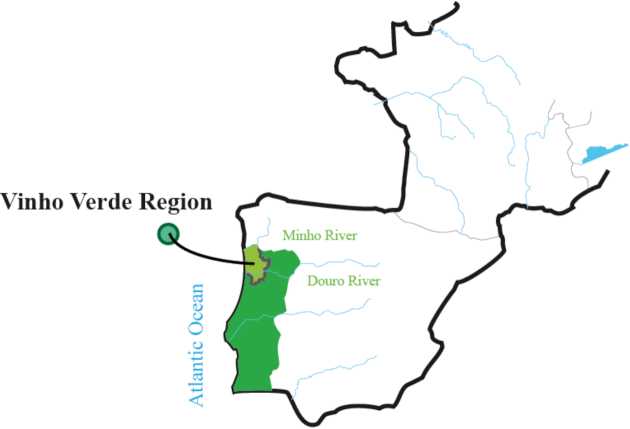

Vinho Verde demarcated region goes from the upper Northwest extreme of Melgaço down until Vale de Cambra, from the coast of Esponsende to the gratinic mountains of Basto, announcing the proximity to Trás-os-Montes region, just on the border of the latter with Minho, forming a region called Entre-Douro-e-Minho,11 meaning “Between Douro and Minho.” Along 7,000 km2 and 21,000 ha of vineyards,12 we behold one of the biggest demarcated regions in Europe13 and the biggest in Portugal, where the green colour appears as the strongest identity mark on the landscape, and so, we find here the reason of the Verde designation of this wine region.14 The following figure shows Entre-Douro-e-Minho region, which boundaries are coincident with the demarcated region of Vinho Verde.

Figure 2. Portugal and Vinho Verde wine region

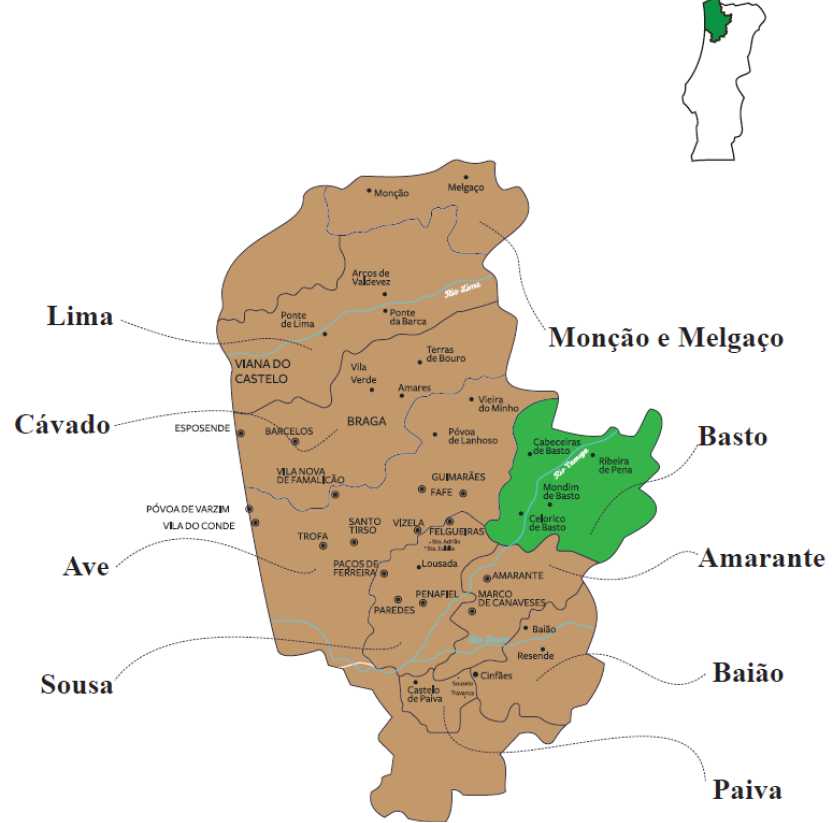

Figure 3. The nine Vinho Verde sub-regions and Basto sub-region

Located in northwest of the country, Entre-Douro-e-Minho region reaches altitudes never higher than 700 meters; it is a region with abundance in water (the green has also this reason), allowing to historical great demographic concentrations and therefore the dissemination of extended farming culture, always characterized by property divisions in relatively small plots of land, where an intensive agriculture activity was developed through an enormous variety of crops and where the hills always have fed the flocks of sheep and goats. In this region where since the III century BC vines are cultivated with regularity and where the wine produced was mainly for household consumption, the economy was always essentially agrarian where since the Middle Ages almost each family had a small plot of land.

Due to great population density and always a great diversity of crops, the vines were let for “secondary role” and to spare space, they were left to grow in the edges of the land plots or in high conduction systems like enforcado (tree-vines), arejão or bardo that are traditional vine training systems of Vinho Verde region. The traditional vine training systems are an important feature of Vinho Verde region landscape, however as this systems were not considered suitable for higher quality wines some years after the EU appellation recognition was established, funds were allocated to restructure those systems by modern ones adapted to the characteristics of the grape variety, having however negative effects on the wine landscapes, unique to Vinho Verde region.

Basto sub-region is one of the 9 sub-regions of Vinho Verde Demarcated wine region. It is constituted by four municipalities, being at the west bank of Tâmega river Cabeceiras de Basto and Celorico de Basto (Braga District) and at the east bank, Ribeira de Pena and Mondim de Basto (Vila Real district) having in total an area of 811,51 km2. Agriculture is still the main economic activity on the region with 67% of the area with a total of more than

4,000 thousand farm holdings. The distribution of population by the municipalities is uneven considering that Cabeceiras de Basto and Celorico contribute with more than 70% of the total Basto region inhabitants. This has an impact in the distribution of wineries knowing that most of the around 30 existent are located in this two municipalities, in which are also registered, obviously, the higher quantities of wine production.

As for the case of Nemea, a four-kind typology was developed after the results analysis.15

1. Production aims mostly international markets in whole world (mostly Europe, United States and Canada) and winemakers work with wine traders.

2. Medium sized production with an exclusive line with a different name and label for international markets, approaching them almost individually without traders. However having the higher percentage of production aiming domestic markets with medium-high quality with exclusive pricing but also more affordable ones.

3. Focusing almost totally in domestic markets with medium quality and affordable prices while having in some cases, although the minority, a single distinct name and label (usually using a Premium tag) for higher pricing.

4. Producing mostly bulk without geographical indications for localized markets of medium and short-channels, and for larger wineries or cooperatives, which bottle it and sell it with their own label.

“Harvesting” Methodological considerations

The entire theoretical framework and methodology was supported on two main hypothesis:

• EU’s policies for rural areas have stimulated more local food networks or have stimulated more industrialised food commodities and;

• EU’s product qualification schemes based on GI’s are able to protect local food and ensure rural development against deterritorialization threats of commodification for larger agro-food chains and markets.

Considering that framework, the complex question “What are the connections between the wine economy and rural development in Basto and Nemea?” was assumed as the main research question.

However, before it was assumed as the main research question, another one had to be resolved: “What wine regions to choose for case-studies and for comparison?” - the answer to this question also justifies why wine was chosen as the product to which food networks were analysed.

First of all, in order to establish pre-conditions for the research to meet potential answers for the above-mentioned first hypothesis, it was decided that the regions to be chosen had to have wine as the only agro-food product with Geographical Indication and Designation of Origin: both Nemea and Basto fulfil this criteria. Therefore, being wine the only product under GIs qualification schemes of the regions, pre-conditions were established to enhance the search for links (or lack of them) between the wine economy, GIs and rural development.

Also, and meeting the second hypothesis, both wine regions have extended importance for the wine economy national-wide. Vinho Verde is one of the biggest wine demarcated regions in Europe and the biggest in Portugal and Nemea is not only one of the biggest in Greece but the most important red wine appellation in the country. Furthermore, in both wine regions considerable changes and challenges have followed countries accession to EU: in Basto restructure on viticulture practices have changed the vineyard landscapes since training systems were completely modified and in Nemea growing economical attractiveness of the region brought newcomers to invest and private wineries, or Estates, to grow significantly.

Nonetheless, not only similarities were seek between the regions to justify choice of regions and to fortify the comparative exercise, but there are also differences: despite agriculture is the main economic activity in both regions and, within this sector, viticulture as the main agricultural activity, Nemean local income comes mostly from wine economy but not in Basto, where services and industry (granitic, wood and transformative) stands as main sources of local income. Besides, Nemea has a local wine cooperative and a local winemakers association, where in Basto none of similar elements exist. For its turn, Basto wine production and commerce is regulated directly by the Vinho Verde Commission as an interprofessional institutionalized body where in Nemea regulations follow directly Agriculture Ministry supervision (even though winemakers association in Nemea aim to become an interprofessional body). At last, Basto was chosen among the nine sub-regions of Vinho Verde region because it is not one of the most striving regions in terms of exports (such as Monção e Melgaço or Lima sub-regions), where there are former research evidences of sub-promotion of this sub-region within the whole region, as will be mentioned further on the text and it is a region where localized networks and short agrofood chains are still significant in production and trade. Besides, in order to fulfil a suitability criteria considering the time constraints (12 months context of a Master thesis research), the proximity of the regions was important for the choice: Nemea is 110 km from Athens where the first author lived while in Greece and his residence in Portugal is located within Basto region.

Considering main research question it was decided to support research on qualitative methods. Therefore it was planned and worked through five steps: Data collection; Interview guide; Choice of the sample; In-depth interviews and data analysis. Data collection was focused on research’s main concepts: terroir; Geographical Indications; Local Foods and Rural Development; Localness and Deterritorialisation; and also on both wine regions existing literature.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out under a framework of two main sections: the evolution of terroir between local knowledge and expert knowledge and the regional and local interprofessional network. The sample was selected accordingly to both convenience sampling and snowball sampling and taking in consideration two criteria: origin of the winery (locally historical embedded or new outcomer) and market orientation (local/domestic or international). In total, 20 interviews were made, in both regions to an equal number of winemakers, wine associations, cooperatives and agriculture governmental authorities.

For Nemea case 14 interviews: six with winemakers, one with the former wine Cooperative, one in a Vine Nursery, one with a public servant from the local agriculture office and one with the Head of the Ministry office that deals with geographical indications. The remaining four were exploratory interviews to prepare better the following ones in Nemea (including the one with the Greek State Secretary for Rural Development already mentioned in this article). For the case of Basto less interviews were made once the time constrained the field research in Portugal, since it was way less than the one spent in Greece.

Therefore, in total 12 interviews: two exploratory interviews (with experts on wine regions and rural development research), eight with winemakers and two at the Vinho Verde Commission (one at the certification and quality control department and one at the marketing department).

The following section, will briefly display the discussion features that define the research problematic in both wine regions so then the main conclusions taken from the interviews analysis can be presented as Potential and Weaknesses as well as interviews excerpts to emphasize the latter.

“Fermentation” Discussion features

In Nemea, the discussion among the winemakers concerned the establishment of sub-zones. Therefore, if formally established, there will be included on the bottles (besides the general Nemea PDO label) certified labelling of the specific rural community (inside Nemea region). We observed that it may result into different status of quality accordingly to different of rural communities of Nemea wine appellation. The opposers16 believe that this changes will have impacts on property values and potentially bringing confusion between consumers regarding Nemea wine.

Besides, the non-participation of Nemea Wine Cooperative on the local association of winemakers (SON) and thus on the main table of the discussion about the changes on the terroir of Nemea, constitutes a problem on the chain of Nemea network. It establishes, at first, a non-communication between the two most important stakeholders in Nemea - the private wineries and the cooperative.

Second, it constitutes a real possibility for, not only the rural community be set apart from the discussion as an important stakeholder, but also an overall consensus over the discussed changes will be almost impossible. This can create a “climate” of distrust and drive the discussion through non-localized “arenas” and thus to deterritorialized decisions.

In Basto there are, increasingly, closer relations between winemakers and bigger companies located elsewhere, than between themselves. This is related with a conflicting competition for stronger network and status, making discussions on common strategies for Basto rural development very difficult to take place.

Furthermore, the predominant relation between winemakers is characterised by individualistic positions. Moreover, it was observed that those positions are augmented by a distrust within the local interprofessional network: meaning a struggle for the same potential clients; to buy (grapes) from vinegrowers with better price/quality ratio and conflicts for better social and political status on the relation with the Vinho Verde Commission.17

Furthermore, the lack of institutional active intermediation (municipal authorities and Vinho Verde Commission) and the inexistence of a Basto wine producers association or even the inexistence of a local cooperative has been leading to the sub-promotion position of Basto on Vinho Verde promotion schemes in comparison with others sub-regions (Lavrador, 2011). It was also evident from the results that the changes on Basto wine sector have been stimulated from outside (in response to international market’s needs) and barely from within - once more, non-localized “arenas” and thus deterritorialized decisions. There is indeed a needed “spark” for all involved actors and local authorities to come together - a necessity of localized governance networks (Winter, 2003).

Therefore, in both wine regions, the existence of localized governance is essential to prevent the negative effects on terroir’s identity and to promote wine production localness through integrated planning involving all stakeholders and political authorities both at local and regional level.

“Bottling” the results Nemea case-study Potentials

Nemea is the bigger appellation in Greece and has domestically and internationally recognised wines for their high-quality and distinctive characteristics. It has a considerable amount of wineries, although there is potential for more, if cutting-edge technology and well-trained and educated oenologists and winemakers will be further allied to the deep-rooted local knowledge and to a striving will to experiment and innovate. It this then a very dynamic region in terms of winemaking.

I am from this area from Nemea area and in the 80’s the Greek wine sector it was not so developed...it was about mainly bulk wine and few major national brands...and you know the pioneers like me and other winemakers they were studying on winemaking and they came back to Greece and without knowing each other they have started to build a new generation, a revolution on the Greek wine (Nemea winemaker).

The existence of SON as a main driver of this knowledge on winemaking dynamic confers a political orientation to the wine sector network in which ideas, projects, proposals, strategical plans for rural and wine tourism have been conceived. The main challenge here lies on the need for SON to focus and stimulate the creation of a same interprofessional association for Viticulture, so then the vinegrowers can have a voice from within and not having necessarily the Cooperative as their representative.

So in 2011 we “deleted”, we abandoned ENOAN, we erased from the map and we founded SON, in this SON the cooperative does not participate because does not want to participate as an entity of the association, in the past the cooperative was stronger, it was like 50% the cooperative, 50% the winemakers...now they were suggested to participate as a single unit, as one of the 34 individuals..they did not accept so they are not in (Nemea winemaker and current President of SON).

Furthermore, the Cooperative has to realised that they cannot sustain their isolated position once their work is essential for the community and the region, not only by being the “last shelter” of the farmers but also to be a needed intermediate between vinegrowers and wineries, where relations of trust are deeply needed so everyone can benefit from the better quality production and share the fair profits within the network.

Weaknesses

The risk of the discussion under sub-zones/sub-appellations appears to be leading into confusion of what “truly” means Nemea and thus, by the nature of the decisions, to a deterritorialization of the product - lack of consensus concerning the changes will have strong impacts at regional and local level.

I am completely opposed to that initiative [sub-zones]. The people that move those things do not know. Each one has its own knowledge of the area and the market and its own general knowledge concerning the environment of winemaking. I am winemaker and oenologist, so I think this initiative would cause way more confusion about Nemea region. There is already the wine named Nemea and people don’t know what it is. If Nemea starts becoming Archaies Kleones, Archaia Nemea, Koutsi, Asprokampos, Gymno what is going to change? We will create a even bigger confusion and a bigger problem to the name Nemea (Nemea winemaker).

Besides the fact that conflict between private wineries and Cooperative is framed by more than just the old ideological opposition of the division of labour relations (public vs private), solidified by history in the political spectrums and social representations, it has been affecting, by negligence, a key actor on the wine sector chain - the farmers that are also representing the local community that is deeply dependent on the wine economy and in fact bears the pillars of that economy.

Of course it is very difficult to communicate with vinegrowers because the way they think...but it is not impossible...you have to make an agreement...a long term agreement, you have to work on it.because there are consequences and you do not need to make a lot of questions...you see it...when you are in an appellation of wine and you go to the market, you go to the Cafe and you will see what the people drink...in winter...how many of them you see drinking Nemea PDO here.or even bottled wine..how many? And using the right glass.how many? Most of them drink whisky or tsipouro..and that is it. This in an appellation and we do not feel it... (Oenologist working in Nemea).

As Papadopoulos wrote about the re-discovery of local knowledge dynamics between the latter and modern scientific knowledge from his research in Nemea:

In terms of rhetoric everyone claims to be using traditional knowledge, and there is nothing surprising about that. Nobody of course denies that modern scientific knowledge and expertise is vital for the production of quality wine and for the diversification of wine production. But to redress the balance many of the winemakers claim, albeit unconvincingly, that: “good wine is produced in the vineyards” (Papadopoulos, 2010: 257).

The main challenge for Nemea is the need for the interprofessional network to place its main focus on “convincingly” believe and work that the good wine is really produced in the vineyards and that to preserve the localness of the production through the vinegrowers capacity to really feel the appellation as they improve in their trust with winemakers and in their viticulture practices fairly paid.

The farmers that come every day to my office that are sad and concerned and they are waiting for me to do something...they are many people who are interested to cultivate more but do not have the right to do that...and here we all have to work for the region, the winemakers, the cooperative and the regional office can do much more if they work together (Public servant at the local agriculture office of Nemea).

This can only be done by the empowerment of the current institutions co-existing with integrated communication, not only for the appellation to be able to provide the desired balanced development for the region but also for the relocalization of local wine in its social, economic and territorial context - which in fact is what is meant by Localness.

Basto case-study Potentials

Basto sub-region has greater potential than current reality expresses since it is agreed as consensual by almost all of the winemakers interviewed that the region has a rare diversity of wine terroir with differentiated micro-climates spread all through the different four municipalities. Furthermore another positive signal is that there are winemakers that not only believe in this but they are also investing in this differentiation, having success in international markets, taking the risk to not to go for undifferentiated wines that can be found anywhere else in the Vinho Verde region. The biggest potential relies on the possible triggering that this initiatives can cause in the already existing winemakers and also to stimulate newcomers to invest in the region.

If we study the Basto sub-region history within Vinhos Verdes region we see that it produces different wines with a different complexity and it’s

probably the sub-region with more terroir diversity and richness of the whole region with a lot of different micro-climates...however there is not still enough wineries going for Premium products more based on quality, not the undifferentiated wines of 10° that lead the exports because they have very competitive prices, cheaper, and they are easier to like because they are sweet and light...but that path does not benefits the region...we have to have more wineries to go for quality wines like our strategy (Basto winemaker).

It also seems that trust relations between some wineries and vinegrowers are better established, at least in some of the rural communities of Basto, than with the case of Nemea, being the dynamics of shared knowledge apparently more fluid. However there is neither a wine cooperative in Basto nor a winemaker’s association.

For example the Cooperative.it failed because there is not associativism...forget!...then there is an unequality...of course that it would be much better if everyone of us would gather and for example for Celorico, there is a given number of vineyards and we will restructure it and we will apply altogether for the restructure of everything...do not even think of that!... (Basto winemaker).

Therefore this relations of trust seem doomed to not experiment the needed full regional integration once there are no local arenas of discussion that could possibly trigger disagreements and consensus within different discussions, like in Nemea.

Weaknesses

There are two main weakness in Basto sub-region that were already more or less addressed. The first is related with the lack of integrated perspective on promotion but also on wider strategies of development. This regards both the winemakers that were never been able to discuss a joint association of winemakers but also on behalf of the local authorities that also do neither have come together for (at least) a intermunicipal strategy of Basto Vinho Verde promotion nor a common strategical plan for the wine sector to be integrated within, for example, the rural tourism sector.

Nothing, nothing, it is impossible so far. No, no...Their minds work like that...like chicken brains...and it is such a pity because there is an enormous potential, because the Basto Sub-region is a region that starts to be known and that makes different wines from the rest of the all Vinho Verde region and therefore with potential to be promoted like that, but I am almost alone in this idea, almost alone (Basto winemaker).

Second, there is a sub-promotion of the identity of Basto sub-region regarding its wine, either due to the first weakness addressed or due to the fact that being integrated in a wider wine region like the whole Vinho Verde in which the institutional promotion is done by a Commission that favours more undifferentiated wines because they are easily exported at lower prices.

There is no control. I will explain you. The Commission has associated wineries and the one who really rule the Commission is a Council which 70% is composed by the biggest Vinho Verde producers, so they rule it as they please...it’s a lobby absolutely indestructible (Basto winemaker).

The cultural heritage that by consensus was considered to exist in a very distinctive way in Basto needs urgently an integrated approach for its protection and promotion so the region can benefit more from this wine sector not only as a source of potential employment and a way to fix people to rural areas, that have been facing decrease in population, but also as a way to make people from Basto to understand that there is a product with a stronger identity from which the whole region can benefit.

So it has not been easy to create cooperative strategies, integrated strategies with producers because we are not many, and it is not only here...and we are still dealing with our own way to deal with our wines inside of the bigger picture of the whole region and not yet focused on integrated initiatives and so...yes...there is not a integrated promotion of Basto sub-region...so there is still a learning process to go through and I am confident we will get there...but we need more producers that come here and believe in the promotion of this sub-region and to believe that this region make different wines and they deserve to be promoted as Basto Vinho Verde (Basto winemaker).

In a matter of conclusion

A tale of two glasses - half empty or half fullThe findings of the research unveiled important clues to answer the main hypothesis, but much more research efforts are needed in wine regions like Nemea and Basto with more extended time, wider and multidisciplinary scope.

Nemea and Basto wine regions have revealed that their wine productions are an asset for rural development through product qualification, which are closely linked to the capacity of GIs to provide an established and legal framework within EU’s policies for rural development. Therefore GIs qualification schemes may provide opportunities for the empowerment of local food networks but simultaneously this opportunities are been captured in both regions by interests that capitalize product qualification to pull out the promotion of the territory for industrialized and commodified strategies and practices. Considering this, and moving on to the second hypothesis, not only GIs appear unfit to protect to all extents local food and, for this particular case, wine terroir, but their framework even enhanced deterritorialization threats hidden under a questionable impetus for rural development revealed in the some discursive traits from the interview results. In other words, personal profit and the gradual shift to larger agro-food chains and markets seems to be a paradigm for economic progress, appropriating GIs intellectual property as a market mechanism, that does not necessarily “happens” in symbiotic relation with the extended development of rural areas in the sense of fair distribution of wine economy revenues and the empowerment of localized agro-food chains.

For both Nemea and Basto cases the main challenge appears to be how to preserve wine terroir and therefore its localness when the interprofessional network is being driven in a way that leads to non-consensual decision-making (Nemea) or isolated modus operandi without discussions at all (Basto). An outmost needed interplay between all the local and regional actors will only play a vital role to preserve localness over deterritorialization if able to mobilize reterritorialization and a re-shaping of traditional knowledge along with winemaking modern techniques. Appropriating the analogy “A tale of two glasses” that Veseth (2011) takes from Dickens book A Tale of Two Cities, we will try to conclude on the question of rural development policies, strategies and actors facing localness vs. deterritorialization.

Starting with the “empty glass”, deterritorialization process is often seen as linked to the rise and dominance of the conventional agro-food chains, and thus, with the globalisation of agro-food system. The other “glass”, apparently, the full one, is seen in terms of local food production and their related GI’s qualification schemes, and related with reterritorialization processes in which regional geographies play a central role to localness of food production along with, the so-called, alternative agro-food chains. Understanding this challenges requires to realise the importance of local networks and actors - from the ones who prune the vines to the ones that bottle the wine that fills the “glasses” - once agro-food system is a configuration that can be analysed by using actor-based notions (Goodman and DuPuis 2002; Goodman, 2004).

In this very last assumption, a focus on actor-based notions and actors networks is crucial to implement rural development strategies conducive to extended development of the region, in a way that all the people involved can be equally part of that process, not just in the terms of the distribution of production and economic revenue, but mainly on a common (and political active) understanding of the network - which means fortifying the roots of the rural development towards an autonomous and democratic rural governance. Remembering Sun-Tzu words in the widely famous The Art of the War, “Bearers of water drinking first indicate great thirst”, one can say, for this case, that when some actors, by their accumulated social capital, holding higher (economic and political) power in the process, (the “bearers of water”) are so thirsty they may “drink first”, without sharing with the local community, it may be merely an indicator of greed but also, and rather important, a regional symptom of isolation and distrust.

Recalling the words from an oenologist of Nemea:

If you do not protect the common nothing works...I understand that everywhere in the world there are conflicts but there is a common thing, a common place that you have to protect.but they [winemakers] have to understand what they have to protect, which I believe they will, but they are doing it in slow steps and we need to go faster towards integrated discussions and initiatives.

[...] otherwise...you see the vinegrowers...they are not feeling the appellation, they do not feel that this is something for them, it does not mean anything for them that Nemea is PDO or not, maybe they do not even know exactly what that means.

Too “thirsty” people, moved by the impatient or simply indifferent pursue for their own isolated profit, will not make “good wine”, generally attracting the “empty glass” of deterritorialization. Yet, there is potential, for they may all drink, one day, from the full one.

Notas

3 When vine growing and producing are translated into a concept like terroir that is embedded by geological and climacteric, territorial, social and cultural characteristics of a rural region, the wine bears a “signature” present on the “natural” and “unique” taste regionally identified that is protected by certified labels of origin.

4 Regarding terroir: “Beyond the measurable ecosystem, there is an additional dimension - the spiritual aspect that recognized the joys, the heartbreaks, the pride, the sweat and the frustrations of its history” (Wilson, 1998 cited by Barham, 2003).

5 Nemea Municipality is part of the Prefecture of Corinthia in which 15 communities are comprised (at 750 m height - Kephalari, Bogikas, Titani, Kastraki, Asprokambos. At 650 m - Psari. At 450 m - Dafni, Petri, Aidonia, Koutsi and two of the rural communities (Gymno and Malandreni both at 300m) are part of Prefecture of Argolida. European Comission legislations says about the borders delimitation of an origin certification label: “Generally, the limits of the area are naturally defined by natural and/or human factors which give the final product its particular. In certain cases, the area will be defined by administrative borders.” (EC, 2002) The latter is the case for Nemea appellation.

6 The equivalent of QWPSR (Quality Wine Produced in a Specified Region). However, VQPRD is known mainly in the wine market for its French designation, it comes originally from the Portuguese Vinho de Qualidade Produzido em Região Determinada, once the first demarcated region of the world is the Demarcated Region of Douro, in Portugal, established by law in 1756. So Portugal was 25 years ahead of France’s 1855 Appellation d’Origine Contrôllée (AOC) in classifying “quality wine”.

7 However accordingly to EU’s wine appellation law, if a maximum of 15% from other grapes is added to the one under the protection of the appellation, being this 85%, the wine is then labelled as another geographical indication, which is Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) under the form of the wider regional unit - being for this case Peloponnese PGI.

8 Despite our several attempts and many visits to Nemea it was not possible to have an interview with any responsible in the Cooperative board of directors, neither from any other department. However we had an interview with the former president of the Cooperative, to which considerations are devoted in the last chapter.

9 We will further refer to winemakers as the owner of private wineries. Whereas for farmers we mean roughly vinegrowers. Even though the latter also make wine, this is generally non-labelled wine being sold as bulk through informal networks. This non-labelled wine is for sure important for the local consumption and local production but it is not, though, the focus of this article, but only Nemea PDO.

10 ENOAN (from the Greek Evroop Oivorcapayroyróv & Aprce^oupyróv Nepéaç) that can be translated into “Nemea Union of Winemakers and Viticulure” was replaced by SON (2/úvôeopoç Oivonoiróv Nepéaç) “Nemea Winemakers Association.” The main reason why there was this change is related with a conflict between the Cooperative and the private winemakers because of a disagreement on how the Board of the Union should be elected Note that the word “viticulture” was dropped in the new name SON. This is also related with the fact that, since the Cooperative is not represented, the vinegrowers and viticulturists are not represented also.

11 11 It was one of six provinces that Portugal was commonly divided into since the early modern period until 1936, then in 1936, when Portugal was divided into 13 official provinces, Entre Douro e Minho was split into Minho Province and Douro Littoral Province. Although, Entre-Douro-e-Minho is not a official territorial unit for administrative purposes, this region is still commonly called this way, specially to refer to Vinho Verdes.

12 In the beginning of the XX century, Vinho Verde Demarcated Region Commission published an extended document to celebrate 100th anniversary of this demarcated region, where it was referred that this region had 35.000 ha of vineyards. This 40% decrease in existing Vinho Verde vineyards is due, partly, to a restructuring in the vineyards to which EC funds contributed, to stimulate quality rather than quantity and partly due to process like de-agriculturalization of the countryside and rural mobilities to urban coastal areas in Portuguese, and of course, also emigration.

13 A legally established demarcated region is known in Europe as VQPRD from the French “Vins de qualité produits dans des régions déterminées” meaning Quality wine produced in demarcated regions. The regions that have legally established wine labels of origin/ protection or qualification schemes like PDO or PGI are firstly recognized under this VQPRD designation. Further considerations on this matter were already developed in previous chapters.

14 It is also considered that the “green” designation comes from the acidity and freshness that characterizes this wine, remembering the flavours of fruits like apple when they are still green.

15 Unfortunately, as for the case of Nemea, it was not possible to add the average production quantities to each one of the wineries types, since both the information gathered through the Commission official data and the one gathered through the interviews were not clear and coincident. Therefore to avoid inaccuracy and confusion it was decided to not mention it. However, this also reveals the lack of institutional trust between the two mentioned parts.

16 Few private wineries, the Cooperative and thus, one can assume, the majority of the farmers (vinegrowers).

17 The commission responsible for Vinho Verde wine certification. Vinho Verde is the designation of the (broader) wine appellation being Basto one of its sub-regions.

References

Baptista, F.O. (2011). “Os Contornos do Rural”. In Figueiredo, E. (coord.). O Rural Plural. Olhar o Presente, Imaginar o Futuro. Castro Verde, Alentejo, 100Luz: 49-58.

Barham, E. (2003). “Translating Terroir: the Global Challenge of French AOC Labelling.” Journal of Rural Studies 19: 127-138.

CEC. (1992). Commission of the European Communities Council Regulation (EEC) No. 2081/92 of July 14.

Covas, A. (2004). Política agrícola e desenvolvimento rural. Temas e problemas. Lisboa, Edições Colibri.

European Comission (EC). (2002). “Indicative Figures on the Distribution of Direct Farm Aid.” EC website:https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/cap-funding/beneficiaries/direct-aid/pdf/annex1-2002-3_en.pdf (consulted in August 15th 2016).

Figueiredo, E. (coord.). (2011). O Rural Plural. Olhar o presente, imaginar o futuro. Castro Verde, Alentejo, 100Luz.

___,(2008). “Imagine there’s No Rural - the Transformation of Rural Spaces into Places of Nature Conservation in Portugal.” European Urban and Regional Studies 15(2): 159-171.

Fonte, M. (2008). “Knowledge, Food and Place. A Way of Producing, a Way of Knowing.” Sociologia Ruralis 48(3): 200-222.

Fonte, M. and Papadopoulos, A.G. (eds.). (2010). Naming Food After Places. Food Relocalisation and Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Development. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Goodman, D. (2004). “Rural Europe Redux? Reflections on Alternative Agro-Food Networks and Paradigma Change.” Sociologia Ruralis 44(1): 3-16.

Goodman, D. and DuPuis, E.M. (2002). “Knowing Food and Growing Food: beyond the Production-Consumption Debate in the Sociology of Agriculture.” Sociologia Ruralis 42(1): 5-22.

Hendrickson, M.K. and Heffernan, W.D. (2002). “Opening Spaces through Relocalization: Locating Potential Resistance in the Weaknesses of the Global System.” Sociologia Ruralis 42(4): 347-369.

Kasimis, C., and Papadopoulos, A.G. (2013). “Rural Transformations and Family Farming in Contemporary Greece”. Research in Rural Sociology and Development 19: 263-23.

___, (2001). “The De-Agriculturalisation of the Greek Countryside: the Changing Characteristics of an Ongoing Socio-Economic Transformation.” In Granberg, L., Kovacs, I. and Tovey, H. (eds.). Europe’s Green Ring. Aldershot, Ashgate: 197-218.

Kourakou-Dragona, S. (2012). Nemea an Historical Wineland. Athens, Foinikas Publications.

Lavrador, A. (2011). Paisagens de Baco - Identidade, Mercado e Desenvolvimento. Estudo de percepção e de representação aplicado às regiões demarcadas: Vinhos Verdes, Douro, Dão, Bairrada e Alentejo. Lisboa, Edições Colibri.

Lazarakis, K. (2005). Wines of Greece. London, Octopus Publishing Group.

Louloudis, L. and Maraveyas, N. (1997). “Farmers and Agricultural Policy in Greece since the Accession to European Union.” Sociologia Ruralis 37(3): 270-286.v

Morgan, K., Marsden, T. and Murdoch, J. (2006). Worlds of Food: Place, Power and Provenance in the Food Chain. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Murdoch, J., Marsden, T. and Banks, J. (2000). “Quality, Nature and Embeddedness: some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector.” Economic Geography 76(2): 107-125.

Papadopoulos, A.G. (2010). “Reclaiming Food Production and Local-Expert Knowledge Nexus in Two Wine-producing Areas in Greece.” In Fonte, M. and Papadopoulos, A.G. (eds.). Naming Food After Places. Food Relocalisation and Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Development. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Ribeiro, J.D., Figueiredo, E. e Soares da Silva, D. (2014). “Ligações Familiares - O consumo de produtos agroalimentares locais em meio urbano: O caso de Aveiro” In Territórios rurais, Agriculturas locais e Cadeias alimentares, Colóquio Ibérico de Estudos Rurais: 79-84.

Santos Varela, J.A. (2007). A Agricultura Portuguesa na PAC: Balanço de duas décadas de integração 1986-2006. Coimbra, Edições Almedina.

Tregear, A., Arfini, F., Belleti, G. and Marescotti, A. (2007). “Regional Foods and Rural Development: the Role of Product Qualification.” Journal of Rural Studies 23(1): 12-22.

Van Leeuwen, C. and Seguin, G. (2006). “The Concept of Terroir in Viticulture.” Journal of Wine Research 17(1): 1-10.

Veseth, M. (2011). Wine Wars: The Curse of the Blue Nun, the Miracle of Two Buck Chuck, and the Revenge of the Terroirists. Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Winter, M. (2003). “Geographies of Food: Agro-Food Geographies - Making Reconnections.” Progress in Human Geography 27(4): 505-513.

Wilson, J.E. (1998). Terroir: the Role of Geology, Climate, and Culture in the Making of French Wines. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Recibido: 9-2-2017 Aprobado: 21-6-2017