RIVAR Vol. 5, N° 15. Septiembre 2018: 176-196.

Artículos

La difusión del vino italiano en los Estados Unidos (1861-1914)

Vegetal Safety in Province of Mendoza Between 1930 and 1950

Manuel Vaquero Piñeiro *

Luciano Maffi **

*Univeristy of Perugia, Perigia, Italia, ORCID 0000-0002-1182-2574, manuel.vaqueropineiro@unipg.it

**University of Genova, Rivanazzano Terme, Italia, ORCID 000-0003-0933-5758, luciano.maffi@unicatt.it

Abstract

During the second half of the 19th century, the world fame of Italian wine began to form. The international exhibitions, the foundation of specialized scholastic institutions, the birth of companies and the technical-scientific divulgation created the conditions of production and marketing of quality wines. The diffusion of Italian wine in the United States is an eloquent example of the changes produced by the internationalization of markets between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. For Italian wine, the United States became a point of comparison and encouragement. A central role was played by the winemaking office created by the Italian government in New York. The objective of the office was to favor wine imports and the circulation of news. The head of the office did an intense job of information but also devoted himself to the analysis of the wine that came from Italy to ensure that it was not adulterated and respected the sanitary norms in force in the country. The action of the office, which even gave advice on the characteristics of the wines, contributed to the formation of a more modern oenological culture among the Italian winemakers who opened themselves to the United States market. All this favored the increase in imports and consumption of Italian wine as shown by the menus of the restaurants. Following the historiographical debate on the effects of the first phase of the globalization of the economy, the objective of the work is to demonstrate that in addition to the massive Italian immigration, the Italian quality wine was consolidated in the United States thanks to a series of initiatives and public and private strategies.

Keywords: Keywords: Italy, United State, 1861-1914, wine, viniculture, international trade.

Resumen

Durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX comenzó a gestarse la fama mundial del vino italiano. Las exposiciones internacionales, la fundación de instituciones escolásticas especializadas, el nacimiento de empresas y la divulgación técnico- científica crearon las condiciones de producción y comercialización de vinos de calidad. La difusión del vino italiano en Estados Unidos constituye un caso elocuente de los cambios que produjo la internaciolización de los mercados entre fines del siglo XIX y comienzos del siglo XX. Para el vino italiano, Estados Unidos llegó a ser un punto de comparación y de estímulo. Un papel central lo jugó la oficina de vinicultura creada por el gobierno italiano en Nueva York: el objetivo de la oficina era favorecer las importaciones de vino y la circulación de noticias. El responsable de la oficina realizaba una intensa labor informativa pero también se dedicaba al análisis del vino llegado de Italia para asegurar que este no fuese adulterado y respetase las normas sanitarias vigentes en el país. La acción de la oficina —que incluso daba consejos sobre las características de los vinos— contribuyó a la formación de una cultura enólogica más moderna entre los vitivinicultores italianos que se abrieron al mercado de los Estados Unidos. Todo ello favoreció el aumento de las importaciones y del consumo de vino italiano, como demuestran los menús de los restaurantes. Siguiendo el debate historiográfico sobre los efectos de la primera fase de la globalización de la economía, el objetivo del trabajo es demostrar que además de la masiva inmigración italiana, el vino italiano de calidad se consolidó en los Estados Unidos gracias a toda una serie de iniciativas y estrategias públicas y privadas.Palabras claves: Italia, Estados Unidos, 1861-1914, vino, vinicultura, comercio internacional.

Italian wine: between tradition and innovation

Despite an abundant harvest of excellent quality grapes, nineteenth century Italy had neither the culture nor the technology to produce quality bottled wines like those of the French, whose domination of international markets went unchallenged (Unwin, 1991; Loubère, 1978). Italian grapes were mainly destined for the production of blended and common wines, to be consumed at the local level. While it is true that Italy had excellent sweet liqueurs, such as Marsala and vermouth, these were unique drinks that resulted from a progressive productive specialization. However, after unification in 1861, when the Italian economy began to deal with the table wine markets of the world, the necessity to break with the past became apparent (Gigliobianco and Toniolo, 2017), in order to address the challenges imposed by the globalization of consumption, above all in the high quality wine sector.

A typical product of Mediterranean agriculture, the transformation of the wine industry saw it occupy a position of great importance in the modern global economy during the second half of the nineteenth century, due to the transport revolution and the integration of commercial channels (Sassatelli, 2017). For the global elite of the Belle Époque, quality European wines—not to mention champagne—became a symbol of status, of an authentic lifestyle that was immortalized in paintings and photographs (Simpson, 2011). On the other hand, the effect that mass migration from European had on the creation of an enological industry far from the old continent should not be overlooked. South Africa, Argentina, Australia and the United States were among the countries that began to carve out a role in the international wine scene at the end of the nineteenth century.

For traditional European wine producing countries, such as France, Spain, and Italy, the increase in competition underlined the need to learn to compete in an increasingly competitive market. Producers had to develop their entrepreneurial spirit and wineries had to be converted from warehouses for the conservation of poor quality wine into genuine industrial plants (Vaquero Piñeiro, 2018). From the seventies of the nineteenth century the industrial cellars developed. In this way, establishments were created with machines and equipment suitable for the production of safe wine. Modern companies demanded large investments and transformed the panorama of wine production throughout the peninsula. The changes were encouraged by the circulation of news from exhibitions, direct observation and company and journalistic advertising. At a time when the global agri-food industry was beginning to take shape, and the mechanisms of food supply chains were being defined (Drouard and Derek, 2009; Segers el at., 2009), this represented a radical change for Italy, and was destined to have an impact on the creation of the modern image of Italian wine, and food in general, in the world (Mariani, 2011).

The hypothesis of this research is that markets such as the United States played a decisive role in the modernization of the Italian wine industry (Pedrocco, 1993). Interest in wine increased in the United States during the nineteenth century (Hannickel, 2013). An example of the ethical vision of agriculture, and the rural identity of the country (Thompson, 2014), can be seen in the passion for European viticulture that Thomas Jefferson expressed in his company in Monticello, Virginia (Hailman, 2006). During the nineteenth century, following the settlement of colonists and religious communities (Fuller, 1999), the spread of vine cultivation provided incentives for informative publications and elegant magazines which, in addition to conveying practical advice, contributed to the development of a romantic vision of the countryside, which besides being profitable, was also to be enjoyed as a pleasant recreational space. In the definition of the American dream, the vine and wine became idealized emblems of entire regions, such as California, which were seen as idyllic agrarian spaces, full of fertile golden valleys covered with lush vineyards, like the ancient hills of Athens or Rome. In the United States in the decades between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there was a growth in both wine production and consumption. The percentages at national level remain low compared to those of the historic producers and consumers of the old world, however they identify a development trend that highlights the changes in custom and production skills that are analyzed in this essay (Alston et al., 2018).

Given these conditions, if Italian wine were to enter the US market, it would have to adapt to the emerging trends in communications and corporate marketing. While Italian enology in the United States could exploit an emerging market in the quality bottled wine sector, bulk wines had little chance of success. The potential demand of Italian immigrants (Choate, 2008) was not sufficient in itself to create a context favorable to the importation of wine. It can be assumed that, for most of the first wave of emigrants that landed in the United States, conditioned by low incomes, and disinclined to spend much money on food by culture (Gabaccia, 1998), wine of a certain quality represented a luxury item for consumption on special occasions (Cinotto, 2013). While the importance of the role that food plays in the construction of identity in immigrant communities should not be ignored (Douglas, 1984), the statistics presented in this paper indicate that, in quantitative terms, there was no direct relationship between Italian immigration and an increase in sales of Italian wine in the United States. “The total volume of wine consumed in the United States almost doubled from 59 ML in 1870 to 106 ML in 1900” (Alston et al., 2018: 418). The theme of the relationship between wine imports and consumption of Italian immigrants remains in the background. In the next studies we will need to establish a clear distinction between bulk wines, table wines and wines for luxury restaurants. For the moment, it is important to underline how the Italian authorities, when they indicated the need to boost sales of Italian wine in the United States, thought mainly of the third category, that is to say wines with a brand aimed at customers with greater 'purchase. These are realities that are not excluded, they can perfectly coexist in defining the characteristics of a diversified market.

That being said, Italian immigrants played a decisive role in the emergence of enology in the United States. As can be seen from the cooperatives that were founded in California, among other states, for many Italians the fledgling American wine industry was an excellent opportunity for social and economic integration, and served, at an early stage, to meet domestic demand for common wine (Amerine, 1975). By contrast, imports involved bottled wines of superior quality, which were aimed at a wealthy and discerning clientele. For Italian producers, accustomed to giving priority to quantity over quality, this was a reversal of perspective.

This contact with the American context demanded attentive care to all aspects of production, in order to adapt to the strict federal food hygiene standards, and provide the customer with information through clear and accurate labeling. It was important to import constant and recognizable typical wines into the United States, which would keep their pleasant aroma and flavor after a long ocean crossing (Harvey and Waye, 2014; Harvey et al., 2014). Thus the United States became a test case for Italy, a country to offer a historical link with the vine, but also a country from which to acquire a more advanced vision. From this point of view, a fundamental role was played by the Oenotechnic station of the Italian government in New York, which he had the task of collecting information and creating a favorable context for Italian wine in the United States, promoting encouragement and marketing initiatives. It was no coincidence that contemporary Italian observers watched the innovations associated with the American business world with interest, in particular in the production and marketing of wine. It was clear that the Italians would have to learn to use the language and techniques of advertising. For all this, as this paper will demonstrate, Italian wine exports to the US constituted a privileged vantage point on two major issues: on the one hand, the transfer of a heritage of wine sector knowledge, which was crucial to the development of the wine industry in the United States, and on the other, the need for Italian producers to meet the challenges of a highly selective market. While the first issue is better known, the second opens up a new field of investigation.

Italian wine after 1861

Even after political unification in 1861, the wine Italian sector was still not able to take advantage of the abundance of raw material available for the production of table wine (Simpson, 2011: 8). The inexperience of the Italian wine industry was demonstrated at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, where Italian wines, compared to their more refined French counterparts, proved far from ready for the opportunities made available by the globalization of trade. It was widely believed that the industry needed a radical change.

When change did arrive, it came from a number of directions. In 1863 the Ministry of Agriculture established the State Oenotechnic Commission, and landowners and merchants were established in many cities of the kingdom, in order to promote the production and marketing of premium quality wines. Another important development was the creation of a ministerial committee to assess the wines that were to be sent to the Vienna International Exposition of 1873 (Annali di viticoltura, 1874: 43-48). A series of winemaking schools were opened in the early 1870s, in Asti, Avellino, Alba, Gattinara and Conegliano, which were responsible for the training of technicians capable of taking a decisive practical and rational approach to vine cultivation and wine production (Monti, 2000). Another factor which imposed a new approach to wine production was that phylloxera, powdery mildew, downy mildew, and other diseases had ravaged continental vineyards from the mid-nineteenth century (Paul, 2002). Italy, which had to its credit the production of millions of hectoliters of wine had, however, still to learn how to manufacture wines that would please the increasingly sophisticated palates of consumers around the world.

Guided by technical innovation in agriculture, Baron Bettino Ricasoli transformed his Brolio castle in Tuscany into a laboratory where Chianti would become the “perfect Italian wine” (Ciuffoletti, 2009). After the results achieved by Ricasoli, the success of “Tuscan wine” was consolidated, and while not everyone could reach the levels of Brolio’s Chianti, the interest in respected table wines increased, bringing an end to the practice of selling off wines due to a lack of demand (Kovatz, 2013). Simultaneously, in Piedmont, companies such as Martini and Gancia also consolidated their position, through a precise separation of the agricultural and the industrial aspects of their business, which obliged farmers to cultivate particular varieties of grapes. In 1878 the wine company E. Mirafiore was the first company established for the production and marketing of Barolo wine, using bottles with a label bearing the name Barolo (Rosso, 2009: 29). These were the first steps towards a turning point that is confirmed by the statistical trends (Federico and Martinelli, 2018; Anderson, Nelgen and Pinilla, 2017).

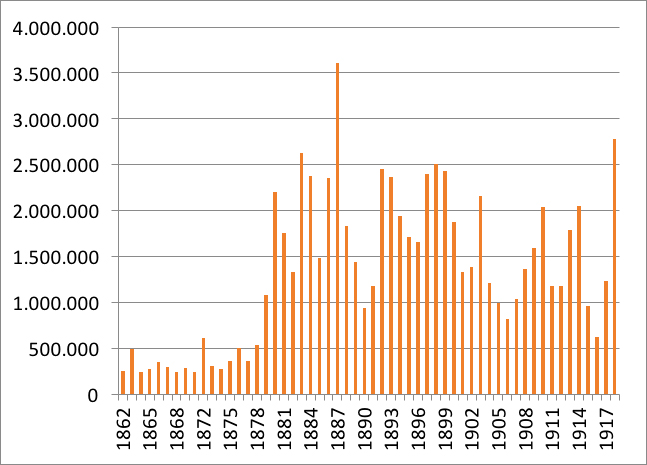

Figure 1. Exports of Italian wine (hectolitres)

Figura 1. Exportaciones de vino italiano (en hectrolitros)

Source: Annuario generale per la viticoltura e la enología; Annali di viticoltura ed enología italiana; Annuario statistico italiano, and Trentin, P. (1985).

Fuente: Annuario generale per la viticoltura e la enologia; Annali di viticoltura ed enologia italiana; Annuario statistico italiano y Trentin, P. (1985).

The data presented in Figure 1 indicates that Italian wine exports did not see any significant improvement until the end of the 1870s (Roccas, 2003; Federico, 1991). From 1879 to 1887 exports increased from one to three and a half million hectoliters. In these years the state of the French market, hard hit by grapevine yellows, led to a steep increase in exports of barreled wines. The decline that occurred between 1889 and 1891 (Figure 2) was a direct result of the Franco- Italian tariff war, which had an extremely negative effect on the robust wines of southern Italy. While the closure of the French market, which was quickly replaced by the Spanish, Portuguese and Algerian markets, damaged the southern regions in particular, at least in the short term (Phillips, 2016: 170), in the long run the Italian wine sector recovered by encouraging the production of quality wines and common table wine, for which there was no shortage of commercial opportunities (Lunardoni, 1904; Dandolo, 2010). In the final decade of the nineteenth century, a recovery in exports took shape, which became stable at between a million and a half and two and a half million hectoliters. In the span of just a few years the markets of Switzerland, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Argentina (Trentin, 1895; Chiaromonte, 1906) managed to replace the French market. After 1900 exports fell below a million and a half hectoliters, and would decline still further between 1905 and 1907, reaching their lowest point in 1906, with just eight hundred thousand hectoliters (Pedrocco, 1993: 336-338). Nevertheless, there was a substantial recovery between 1908 and the years immediately preceding the outbreak of The First World War, due to a sharp contraction in prices, which reached a high point in 1914, when exports once again exceeded two million hectoliters. With the outbreak of hostilities, Italian wine exports once again began to decline drastically, a drop that lasted a couple of years, but by 1919 Italian wine exports once again showed strong signs of growth, until they reached unprecedented levels.

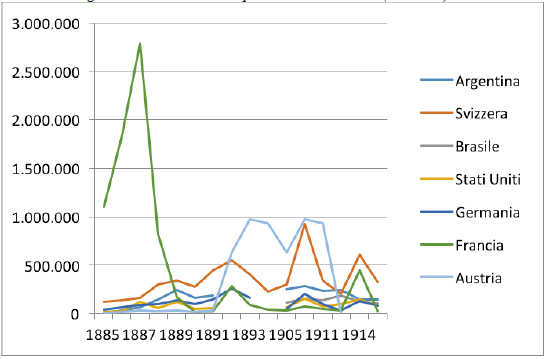

Figure 2. Leading importing countries of Italian wine (1885-1915)

Source: Annuario generate per la viticoltura e la enología; Annali di viticoltura ed enología italiana; Annuario statistico italiano, and Trentin, P. (1985).

Fuente: Annuario generaleper la viticoltura e la enologia; Annali di viticoltura ed enologia italiana; Annuario statistico italiano y Trentin, P. (1985).

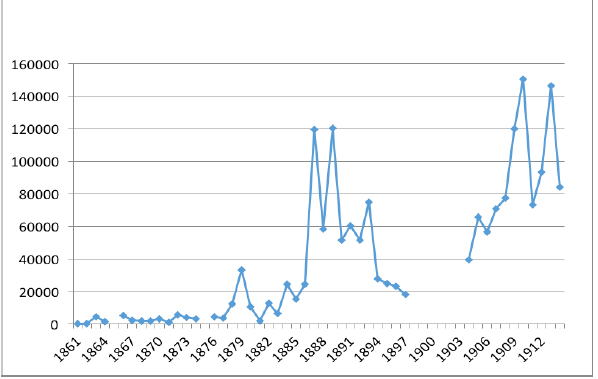

Looking at the American market in particular, in 1861 Italian wine exports to the US amounted to scarcely 4 hectoliters (Figure 3). During the 1860s and 1870s the situation improved, with exports averaging around 2.400 hectoliters, with peaks of 5.135 (1866) and 5.790 (1872) hectoliters. The first change in the trend came after 1878, when imports of Italian wine reached 33,016 hectoliters, a positive development that continued after 1884. In the unstable oenological market, the recorded average of Italian wine exports to the US between 1885 and 1893 was about 63.000 hectoliters. The last years of the nineteenth century saw a drastic fall after 1894, down to 18.282 hectoliters in 1897. The early twentieth century saw a rapid recovery: 65.812 hectoliters in 1905, and in excess of 100.000-150.000 hectoliters in 1910 and 1914. With regard to exports of bottled wines, they rose from barely 5,000 in 1874 to 250.000 units in 1881, and 629.000 in 1890. The main types of Italian wine exported to the US were Barbera, Chianti, Barolo, Capri, Lacryma Christi, Asti sparkling wine, and Moscato di Siracusa, as well as the traditional Marsala and Vermouth (Hancock, 2009). Unfortunately, the statistics do not allow to establish quantitative distinctions between the different types of imported Italian wine. In percentages, in the best years immediately prior to World War I, wine exported to the United States accounted for 7-8% of the total world exports of Italian wine. At the end of the nineteenth century the United States, together with Brazil, Argentina, Germany and France, became among the top five international markets for volume of Italian wine bottles.

Figure 3. Italian wine exports to the United States 1861-1915 (hectolitres)

Figura 3. Exportaciones de vino italianas hacia Estados Unidos 1861-1915 (en hectolitros)

Source: Annuario generale per la viticoltura e la enología; Annali di viticoltura ed enología italiana; Annuario statistico italiano, and Trentin, P. (1985).

Fuente: Annuario generale per la viticoltura e la enologia; Annali di viticoltura ed enologia italiana; Annuario statistico italiano y Trentin, P. (1985).

In addition to suffering the negative consequences of the prohibitionist propaganda that was beginning to impose limitations on the consumption of alcohol (Hames, 2012; Mendelson, 2009), there was also an impact on wine imports as a result of the application of the “Pure Food and Drugs Act” (1906), which dealt with substances harmful to the public health and the marketing of food products (Rumbarger, 1989). Specifically the measure required that even low amounts of sulfur dioxide be declared on the label of the bottle, even if the quantities were lower than the limits set by the regulations. The measures taken by the federal authorities hit Chianti in particular (Mocarelli, 2013). This was a wine that had some success among the American elite, but to be fully accepted the rate of alcohol had to be lowered to a maximum of 12%. It also had to adapt to the taste of the country, as American customers were looking for smooth, less austere, palatable wines (Ottavi and Marescalchi, 1897: 313). While such constraints may not initially have appeared to help Italian wine exports to the United States, they also had a positive effect, as Italian winegrowers that were more open to innovation and adapted their product according to the health and food hygiene legislation in export markets, reducing the rate of alcohol and ensuring the quality of the bottled product, in order to meet the requirements imposed by the regulations. As can be seen from these notes, the history of the diffusion of Italian wine in the United States admits many research trails that also include the production by the immigrants themselves or the falsifications already practiced since the end of the century. So the wine is confirmed as an excellent key to improve our knowledge on the many aspects that surrounded the creation in the United States of an image of Italian food products.

The market penetration of Italian wine in the United States: The Oenotechnic station of the Italian government in New York

The international exhibitions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were not only opportunities for the promotion of Italian wines. They also encouraged innovation, change and a comparative approach (Teughels and Scholliers, 2015). Within a few decades, “local” food products became “global” and “typical”. The overseas exhibitions were also of particular importance, as they were an opportunity to experiment with the ability to conserve wine on long journeys, and overcome its perishable nature, an essential requirement to enter previously untried new markets.

This was the context of The Centennial International Exhibition, which was celebrated in Philadelphia in 1876, and attended by 148 Italian wine producers, with a clear predominance of Sicilians and Tuscans. The Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 (Bolotin and Laing, 2002; World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893; Rossiter, 1898: 115) was host to 65 exhibitors of Italian wines, which earned particularly positive comments:

Italy exhibited all its types of wine, including the heavy bodies, still and sparkling wines of the northern mountains, the clear, well-tempered Chianti of Tuscany, the rougher clarets of the Apennines, Marsala and the Sicilian country wines, and the various choice vintages of Vesuvius and the Neapolitan islands (Dubois, 1901).

Another opportunity for a point of comparison between Italian winemaking and the American context was the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 (Official Catalogue, 1904: 247-250). Of 58 wine exhibitors in Saint Louis, the largest number were from Puglia (17), followed by Tuscany (11) and Sicily (10), then Piedmont (5), Campania (5), Calabria (2), Abruzzo (2), Molise (1), Lazio (1), and another four of unrecorded origin. Unfortunately, the catalog generically made reference to “wines”, without any indication of the types of wine being promoted. Barolo and Barbera wines are only specifically referenced once each (Final Report, 1906: 216).

While Italian wine producers had an important presence at the major international exhibitions in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, the number of participants fell from 148 in Philadelphia in 1876 to 58 in Saint Louis in 1904. This contraction can be explained as the logical consequence of the costs involved, and also because the international exhibitions, once the novelty had passed, brought with them their own issues, such as the selection of participants, limited to those that could effectively invest in order to enter new and distant markets. While there were obvious difficulties to be faced, from the perspective of the Italian producers, the final reports from American fairs show an awareness of the importance of Italian viticulture. American exhibitions were, therefore, a driving force in opening up to new markets, as they incentivized relations, favoring the exchange of information and the development of skills. Visiting the exhibitions was an important stimulus for innovation, change and comparison for Italian wine entrepreneurs, government representatives and local institutions, and also in terms of human capital, through education and the diffusion of knowledge.

One of the most important initiatives taken to encourage the success of Italian wine involved the Oenotechnic stations of the Italian government. While initiatives such as schools and travelling teachers aimed to encourage cultivation and rational production, the Oenotechnic stations, launched in a number of large cities, such as London, Buenos Aires, Zurich, Budapest and New York, were designed to increase sales, open new markets and provide manufacturers with technical and marketing support. The overseas Italian Oenotechnic stations, led by wine industry experts, were responsible for gathering information on the legislation in the target countries, customers' eating habits, pricing, and distribution channels, in order to encourage the promotion of Italian wine in shops and restaurants. The station managers were not supposed to intervene in commercial operations, but rather put themselves at the service of those who, for a fee, needed to perform an analysis of wines. Indeed, one of the main obstacles to overcome was to win the confidence of buyers, both wholesale importers and simple clients, and reduce the risk of fraud and counterfeiting. Certificates issued by the Oenotechnic stations included an analysis of the characteristics of wines, beginning with the level of alcohol. All barrels and bottles had to bear a stamp and a label confirming that their contents had been checked. Such measures had the clear objective of certifying that the wine was safe and from the specified place of origin. Therefore, the Oenotechnic stations made a decisive contribution to imposing a modern wine culture on Italian producers, to help them avoid missing out on the opportunities they had earned, having learned to make good quality, consistent, typical wines. From this point of view, the role of station managers was fundamental in codifying the organoleptic characteristics of what could be defined as a good typical Italian wine. Some of the properties that Chianti had to possess to be accepted outside Italy included being clear and light, with a ruby color frank taste.2 The New York station was decisive in the definition of the characteristics of Italian wine, and also gave the authorities and Italian winemakers the opportunity, through regular informational publications, to learn about the agricultural context of a country where the principles of modern industry were also applied to wine production. For late nineteenth century Italian viniculture, which remained linked to artisanal production, this was a real challenge.

The New York Oenotechnic station was entrusted to Guido Rossati in 1895. Rossi had previously been Deputy of the Italian Government for Italian Wines in London, with a mandate to make the characteristics of Italian wines better known in England (Rossati, 1888). In the United States he devoted himself to the publication of articles on Italian wines in the local press3 and was the author of an extensive study of the cultivation of vines and wine production in the United States (Rossati, 1900).4 In this volume, the result of an expedition across the country, the head of the Oenotechnic station of the Italian government offers a variety of information on the wine-growing conditions in every state in the union, emphasizing in detail the environmental characteristics and the quality of the rail and maritime infrastructure that was fundamental to increasing exports. Special attention was reserved for the development of viticulture in the California (Hittell, 1882: 244-246). For Rossati these measures were to be taken as an example, as they made it possible to combine theory and practice, a key aspect in the transformation of wine production into an industrial activity. It was no coincidence that the representative of the Italian government verified that some entrepreneurial activities conducted by Italians, such as the Swiss-Italian colony in Asti, were in a position to make a key contribution to the development of a national wine industry. In particular, the Swiss-Italian colony was responsible for the introduction of Italian red wines in California, in particular those from Piedmont, such as Barbera, Nebbiolo, Muscat, Bonarda and Refosco, which was marketed as Crabb’s Black Burgundy.

If the environmental conditions made California an ideal region for the production of large quantities of wine (Walker, 2005), another aspect that appealed to the head of the Italian Oenotechnic station was the superior technological capability that American wine producers possessed. Their mechanical workshops planned and constructed machinery capable of moving large quantities of grapes, while the automation of work enabled considerable manpower savings. Rossati’s idea was that Italian vintners would acquire new information through magazines and specialized publications, or, better yet, take educational trips to observe in person the facilities that made the production of wine more convenient, in terms of both time saving and manufacturing costs (Rossati, 1900: 319-322). The work carried out by Rossati as director of the New York station shows that the role played by the state in the globalization of the Italian wine industry should not be underestimated. The internationalization of products was achieved through a variety of roads (Fumian, 2016). For the more enterprising producers the news coming from the United States, to be read also in the newspapers, represented a sure point of reference but also a constant stimulus to innovations.

Another factor that Guido Rossati attributed with the success of viticulture in California was the role of the press. The publications that addressed the problems of the wine industry were distinguished by their large print runs, the originality of their features and documented articles. For Rossati the role of the press was fundamental, for the in-depth articles but also for the announcements that allowed a wide diffusion of the news. Therefore the director insists that also in Italy the oenological sector must have specialized newspapers and magazines. The same considerations also applied to the Italian language newspapers printed in San Francisco. These were newspapers intended for immigrants, which had a clear function as a point of reference, and for the transmission of information beyond the barriers imposed by the use of English. Thus for Italian immigrants, California offered the conditions for practicing a more advanced viticulture, which also demonstrated the road ahead for Italy. In conclusion, Guido Rossati’s book constituted a clear example of how Italian viticulture needed to draw lessons from the situation in California, as an impetus and stimulus for change.

For Italian enological technicians, who began to emerge from the agricultural colleges of Conegliano, Alba, and other educational institutions in the late nineteenth century, the expansionary American wine industry offered excellent professional opportunities, as long as they were able to overcome the first hurdle, which was the necessity of a good command of the English language (Rossati, 1900: 327). In terms of language training, Italian schools of agronomy had glaring shortcomings, which prevented students in possession of a diploma from being able to practice their profession outside Italy. This was an educational limitation for which it was not easy to find a solution, as the syllabus set by government bodies addressed full attention to technical and scientific subjects, at the expense of others, such as foreign languages. As a result English was decidedly overlooked.

That being said, the difficulties facing Italian wine technicians who wanted to practice their profession in the United States did not stem from their language skills alone, as they also had to overcome other limitations in their training. In particular there was a widespread lack of knowledge about enological mechanics. While they had a solid theoretical background in plant cultivation, Italian oenology graduates appeared to lack expertise in terms of the machinery needed to transform wineries into efficient production sites. Even the straightforward use of steam engines represented an absolute innovation for many Italian technicians. In order not to miss out on concrete job opportunities, Italian wine technicians that were prepared to participate in the competitive US market had to demonstrate the humility to accept employment at a mechanical plant, where they could hone their skills without the higher social status that might be expected as the holder of a prestigious academic title (Rossati, 1900: 328). However, despite such obstacles, it was still possible to enter the American labor market, as demonstrated by the professional trajectories of a numerous generation of Italian wine technicians who, once they had left the classrooms of Conegliano or Portici, found work managing renowned Californian wine companies.

One of the fundamental aspects of Guido Rossati during of his inspection was to know personally the situation of Italian colonies founded by Italians for whom, for reasons of identity, the cultivation of vine and the production of wine was something natural. It also allowed to maintain a symbolic link with the country of origin through one of the most emblematic products of the regions of origin (Cinotto, 2012). The arrival of Italians in California had already been documented by the mid-nineteenth century, before the great wave of immigration that followed at the end of the century. They were attracted by the positive social and economic conditions for agricultural and commercial activities (Rosano, 2000: 30-31). During the second half of the nineteenth century agricultural holdings were transformed into wineries by immigrants, who found the right conditions to achieve maximum results from a consolidated wealth of experience and knowledgein their adopted country.

In the vast and multifaceted panorama of the great influx of Italians which occurred in the late nineteenth century United States (Fauri, 2015: 116-133), the creation of agricultural colonies intended to provide new arrivals with a place of work constituted a matter of significant interest, for a number of reasons. Indeed, at the same time that many entrepreneurial initiatives were launched at the end of the nineteenth century, which in many cases would be consolidated during the next century, Italian immigration was also involved in the birth of new forms of association, with ideals inspired by Catholic associations. It was important for the agrarian colonies in the United States to have a social role, sometimes of a utopian- socialist nature (Calderone, 2013), in giving work and comfort to their many countrymen who had been attracted by the lure of easy money, and then ended up caught up in the perils of life in the large cities (Baily, 1999). Diplomatic representatives of the Italian Government, called upon to complete fact finding trips to learn about conditions for their countrymen who had moved to the new continent (Milani, 1993), emphasized the dangers of emigration to the big cities, suggesting, conversely, the convenience of diverting people towards rural settlements, which were better suited to the roots of emigrants. The agricultural colonies, from this point of view, seemed the most appropriate solution, as they offered newcomers the opportunity to lead an honest life in the countryside, far from the high prices and the dangers of urban life (Vezzosi, 2012).

The agrarian colonies proved the ideal instrument to achieve these objectives. This was the context of the Italian Swiss Colony of Asti, which was founded in California in 1881 by the Ligurian Andrea Sbarboro. (Pinney, 1989: 327-329; Florence, 1999; Bosi, 2013: 222-223) Sbarboro was able to perform a beneficial action through wine production, while offering the nascent national wine industry a point of reference (Rossati, 1900). The winery had a cellar capable of holding up to 250.000 gallons of wine, and the monumental brick building in San Francisco, which housed stores and offices, and constituted a concrete testimony of the results they achieved. The Italian-Swiss colony managed the entire wine cycle, from harvesting to commercialization, and found itself in a position to expand its business, moving into urban markets in New York, Chicago and New Orleans. Above reference to “a numerous generation of Italian wine technicians who, once they had left the classrooms of Conegliano or Portici, found work managing renowned Californian wine companies” (Rossati, 1900: 315) would be useful to identify, if possible, some of those wine companies.

The model of collective agricultural labor brought over from Italy also found the right conditions to advance in other states. This was the case of the Lambert and Daphne agricultural colonies in Baldwin Country, Alabama (Ruvoli, 2010). Founded in 1888 by Alessandro Mastro Valerio, publicist and senior editor at the Tribuna italiana in Chicago, they had the goal of allowing Italian farmers who had immigrated to the United States an opportunity to return to agricultural activity, while providing them with a chance to move away from “the often pernicious and demoralizing influence of the great American cities”. The production of wine in the Italian colonies in Alabama continued until the enactment of the prohibition laws of the 1920s, a measure that forced them to replace the vine with other plants, such as citrus fruits (Pinney, 1989: 412). Alessandro Mastro was the author of a number of articles published in the agricultural almanac L’agricoltore calabro-siculo. This confirms that the agricultural experience of Italians in the United States was used to publicize this progress and the knowledge of modern agronomic science in Italy (Vaquero Piñeiro, 2015).

Another example of an Italian agricultural colony in the United States was the Vineland colony in New Jersey, founded in 1873 at the behest of Gian Francesco Secchi de’ Casali from Piacenza. At the beginning of the twentieth century a population of about 6,000 people were brought together from a thousand farm families from Venice, Emilia, Campania, and other regions of the Italian peninsula (Pollice et al., 2015; Hahamovitch, 1997: 55-78).

The construction of the image of Italian wine

The birth of a new generation of wine entrepreneurs in Italy at the end the nineteenth century represented an innovation of considerable importance, which marked the passage of the wine sector from a craft to an industry. It was generally agreed at the time that the French had a consolidated advantage, not only with regard to wine production, but above all in terms of sales, demonstrating a greater preparation to adapt to the characteristics of target markets (Garrier and Pech, 1994). It is worth noting that in Italy in the 1880s a label on a bottle was described as a “card” and treated as an object of curiosity (Enotrio, 1879), an example of the considerable cultural distance that existed between the two countries. In the Italian case it was necessary to build an entire economic sector from scratch. Still at the end of the 19th century, for many merchants and producers, commercial techniques represented an absolute novelty. The essential requirements needed to successfully promote a delicate product such as wine on the international scene were lacking. The intermediaries were local and the buyers did not give up the practice of tasting the wine before agreeing on a price. It was clear that foreign markets required broader knowledge, less related to personal relationships and more based on product reputation. Very few companies were concerned exclusively with the distribution of wine.

The context was certainly influenced by the weight of tradition but at the same time, just in the field of commercial communication, new developments began to take place. A double reality was created. From a high production linked to the local market and on the other hand the growth of operators urged by the international market. As the advertisements show in the main newspapers in the main foreign cities (Buenos Aires, London, New York) the Italian wine producers began to collaborate with agencies and specialized personnel able to manage the deposits, to relate with local distributors and to follow all import-export practices. They are new professional figures that face the labor market. Cella Bros in New York, Charles Ciceri in Montréal, Fratelli Romeo in New York, and Vincent Bosco in New York were just a few of the Italo-American companies founded in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that came to command a commercial area that was still being defined. For Italian observers it was clear that the American market was a test case, as the growing production of wine in California indicated that Italy could gain an advantage by concentrating on the export of high quality typical wines, the only product able to compensate for the high cost of transport and customs duties. As the consumption of alcoholic beverages of a certain social standard appeared to be closely tied to the level of disposable income (Coit Chapin, 1909: 133-135), the US market was not going to be conquered by concentrating on quantity, but rather on quality, and the adaptation of new marketing and advertising techniques capable of orientating the consumption of the sectors of society with greater spending power, which naturally included wealthy Italians (Lunardoni, 1904: 45).

This was the case, for example, of Pontin’s Restaurant, a well known New York establishment (Grimes, 2009: 77-78) that advertised Italian cuisine served in an authentic Italian style garden in the pages of the Italian chamber of commerce magazine in New York,5 just a few meters from the courts and trading companies. Along with a wide range of French and German wines, the wine list also included a selection of Italian wines, above all Chianti, but also Muscat, Nebbiolo, Lacryma Christi, and other wines from the south of Italy. It appeared equally fundamental that Italian wines find a place on the menu of luxury restaurants,6 aimed at a wealthy clientele that represented the measurement parameter of the market penetration of Italian wine in the cities of the United States.

It was also necessary to master the nascent techniques of advertising, as for wine, a product rich in social and cultural values, to be sold, it was not enough for it to be of good quality and well priced. It was also necessary for wine to have a recognizable name, which associated it with the scenic and artistic characteristics of the Italian regions. This was already regarded as an excellent promotional vehicle for both Italian wine and its country of origin by the end of the nineteenth century. Enological réclame in Italy became the topic of debate among specialists, with a progressive increase in exports of bottled wine, which needed to be differentiated with a label, featuring the name of the wine and a captivating brand. While still nowhere near American standards of brand recognition, for Italian wines this was the beginning of a long path of growth in dealing with the changing tastes of customers in geographically distant markets (De Grazia, 2005). Wanting to satisfy the lifestyles of the emerging classes of the Belle Époque, and to overcome the traditional view of wine as a popular drink (Capuzzo, 2006: 243¬251), advertising was entrusted with the creation of a stimulating image for quality wine, to give it a distinguished position in restaurants, official lunches and, not least, in the daily life of the family. Nothing was to be left to chance, and while the French had access to a large and proven repertoire of evocative chateaux (Grappe, 2013), a testing ground was created for Italian graphic artists, combining realistic and allegorical elements.

The bottles had to be elegant, with meticulous attention to detail in the presentation, and labels capable of reflecting the country’s artistic tradition, drawing inspiration from Italy’s many natural wonders. The illustrators called upon to design the image of such a symbolic product had a wide range of themes at their disposal, from which to draw inspiration: the coats of arms of royal houses, floral decorations, works of art, ancient buildings, mythological scenes, and most of all beautiful scenery, such as Vesuvius, the Gulf of Naples and Mount Etna, all of which were easily identifiable.

In this way, the landscape became both the instrument and object of communication, helping to create the typical image of Italian wine. For the young unified Italy, which was opening up to world trade, wine advertising was transformed into a story in which allegorical images presented Italian products as elements of an almost mythical, dreamed world, transporting the consumer to a sort of commercial Eden (Piazza and Bellanda, 2014: 10).

Conclusions

At the time of unification, the Italian wine industry was in an inadequate position: a rational system of vine cultivation was lacking, the wineries were technologically underdeveloped, and the commercialization of wine was mostly in bulk, and not in bottles.

In the light of the context that has been presented in this article, it can be said that the theory that the consumption of Italian wine in the United States was almost exclusively due to the growing number of immigrants of Italian origin does not fully explain why the main types of wine exported to the United States were high quality bottled wines, such as Barolo or Chianti. A key role was played by Italian experts, who trained at schools along the peninsula and emigrated to the United States. They were able to combine their excellent Italian education with the technology and economic resources made available to them in America. This winning combination ensured the development of a high quality product that contributed to the growth of the US wine sector, as was already evident at the beginning of the twentieth century. The stringent US health and hygiene regulations were also applied as a product quality benchmark in Italy, guaranteeing the production of high quality wines, and the use of cultivation and wine making techniques that were noteworthy at the international level.

In conclusion, the historiography of the sector can be studied from the viewpoints stated above, in order to better understand the complexity and the bilateral nature of the ties between the two nations, and the relationships which led to the exchange of information and knowledge that was at the foundation of the growth, innovation and development of the wine sector on both continents. It can be said that while the United States played a leading role in the technological and commercial spheres, Italy was able to express its long established expertise in oenological culture, and an entrepreneurship rooted in centuries of wine production experience.

Notas

1 La plaga de filoxera se propaga de diversos modos, tales como el agua de riego adherida al calzado de los trabajadores, por medio de las aves, pájaros, perros, herramientas de trabajo, con plantas raizadas o por las grietas y poros de la tierra. Además facilita la difusión de la enfermedad la misma reconstitución de los viñedos, pasándose de una explotación a otra (Vinos, Viñas y Frutas, 1946).

2 Archivio Centrale dello Stato (Italy, Rome) = ACS, Ministero di agricoltura, industria, commercio = MAIC. Direzione generale dell’agricoltura, VI versamento, b. 458, fasc. 2267, 8.

3 ACS, MAIC, VI versamento, b. 468, fasc. 2300.

4 Pompeo Trenti, director of the Italian oenological station in Buenos Aires, in 1892 made a travel to Argentina and Chile to learn about the viticulture of these countries. The result of the journey is a long (yet unprecedented) technical report on vine cultivation and wine production, ACS, MAIC, VI versamento, b. 462.

5 Weekly Bullettin of Italian Chambers of Commerce of New York, XX, 2, 1919.

6 Visit http://menus.nypl.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2018).

Bibliografía

Alston, J.M, Lapsley, J.T., Sambucci, O. and Sumner, D.A. (2018). “United States”. In Anderson, K. and Pinilla, V. (eds.). Wine Globalization. A New Comparative History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 410-440.

Amerine, M.A. (1975). “The Napa Valley Grape and Wine Industry”. Agricultural History 49(1): 289-291.

Anderson, K., Nelgen, S. and Pinilla, V. (2017), Global Wine Markets 1860 to 2016. A Statistical Compendium. Adelaide, The University of Adelaide.

Annali di viticoltura ed enologia italiana. (1874). III, 5, fasc. 25, 43-48.

Annuario generale per la viticoltura e la enologia. (1892-1893). Roma: Circolo enofilo italiano.

Annuario stadistico italiano. (1878-1915). Roma: Instituto céntrale di stadistica.

Baily, S. (1999). Immigrants in the Land Promise. Italians in Buenos Aires and New York City, 1870-1914. Ithaca-London: Cornell University Press.

Bolotin, N. and Laing, C. (2002). The World’s Columbian Exposition: the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Urbana: University of Illinois press.

Bosi, A. (2013). Cinquant’anni di vita italiana in America. London: Hard Press Publishing.

Calderone, G. (2013). “Il progetto delle colonie agricole negli Stati Uniti della grande emigrazione”. Altreitalie gennaio-giugno, 31-56.

Capuzzo, P. (2006). Culture del consumo. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Chiaromonte, T. (1906). Il commercio dei vini nella Repubblica Argentina nel decennio 1895¬1904. Istruzioni e consigli agli esportatori italiani. Roma: Tip. nazionale G. Bertero e C.

Choate, M.L. (2008). Emigrant Nation. The Making of Italy. Abroad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cinotto, S. (2013). The Italian American Table. Food, Family and Community in New York City. Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press. ___, (2012). Soft Soil, Black Grapes. The Birth of Italian Wine making in California. New York: New York University Press.

Ciuffoletti, Z. (2009). Alla ricerca del “vinoperfetto”. Il Chianti del barone di Brolio. Ricasoli e il Risorgimento vitivinicolo italiano. Firenze: L. S. Olschki.

Coit Chapin, R. (1909). The Standard of Living among Workingmen’s Families in New York City. New York: Charities Publication Committee.

Dandolo, F. (2010). Vigneti fragili. Espansione e crisi della viticoltura nel Mezzogiorno in età liberale. Napoli: Guida.

De Grazia, V. (2005). Irresistible Empire. America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Douglas, M. (1984). Food in the Social Order. Studies on Food and Festivities in Three American Communities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Drouard, A. and Derek, J.O. (2009). The Food Industries of Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Routledge.

Dubois, E. (1901). “History of the Vine, the Grape, and the Wine”. In World’s Columbian exposition, 1893. Report of the Committee on Awards of the World’s Columbian Commission. Special reports upon special subjects or groups. Washington D.C.: Gov't Print. Off.

Enotrio, I. (1879). Manuale del venditore e compratore di vino. Casale: Tip. Cassone.

Fauri, F. (2015). Storia economica delle migrazioni italiane. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Federico, G. (1991). “Oltre frontiera: l’Italia nel mercato agricolo internazionale”. In Bevilacqua, P. (ed.). Storia dell’agricoltura italiana in età contemporanea. III. Mercati e istituzioni. Venezia: Marsilio, 189-222.

Federico, G. and Martinelli, P. (2018). “Italy to 1938”. In Anderson, K. and Pinilla, V. (eds.). Wine Globalization. A New Comparative History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 130-153.

Final Report of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Commission. (1906). Washington D.C.: Louisiana Purchase Exposition Commission, Gov’t print. off.

Florence, J.W. (1999). Legacy of a Village. The Italian Swiss Colony Winery and People of Asti. California: Raymond Court Press.

Fuller, R.C. (1999). Religion and Wine. A Cultural History of Wine Drinking in the United States. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Fumian, C. (2016). “L’Italia e la mondializzazione degli scambi di tardo Ottocento”. Storia contemporanea 282: 18-44.

Gabaccia, D.R. (1998). We are what we eat. Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Garrier, G. and Pech, R. (1994). Genèse de la qualité des vins - L'évolution en France et en Italie depuis deux siècles. Chaintré: Oenoplurimedia.

Gigliobianco, A. and Toniolo, G. (2017). “Concorrenza e crescita in Italia”. In Gigliobianco, A. and Toniolo, G. (eds.). Concorrenza, mercato e crescita in Italia: il lungo periodo. Venezia: Marsilio, 3-39.

Grappe, Y. (2013). “Perché sei cosí buono? Storia e percezione della qualità del vino tra Francia e Italia”. In Cipolla, C. (ed.). Il Maestro di vino. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Grimes, W. (2009). Appetite City, a Culinary History of New York. New York: North Point Press.

Hahamovitch, C. (1997). The Fruits of Their Labor. Atlantic Coast Farmworkers and the Making of Migrant Poverty, 1870-1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Hailman, J. (2006). Thomas Jefferson on the Wine. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Hames, G. (2012). Alcohol in World. History. London and New York: Routledge.

Hancock, D. (2009). Oceans of Wine. Madeira and the Emergence of American Trade and Taste. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Hannickel, E. (2013). Empire of vines: Wine culture in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Harvey, M., White, L. and Forst, W. (2014). Wine and Identity: Branding, Heritage, Terroir. London-New York: Routledge.

Harvey, M. and Waye, V. (2014). Global Wine Regulation. Pyrmont, Lawbook Co.

Hittell, J.S. (1882). The commerce and industries of the Pacific coast of North America. San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Co.

Kovatz, S. (2013). “The Geography of Quality Wine in United Italy Areas and Producers”. In Ceccarelli, G., Grandi, A. and Magagnoli, S. (eds.). Typicality in History. Tradition, Innovation and Terroir. La typicité dans l’histoire. Tradition, innovation et terroir. Brussels: Peter Lang, 305-321.

Loubère, L.A. (1978). The Red and the White. The History of Wine in France and Italy in the Nineteenth Century. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lunardoni, A. (1904). Vini, uve e legnami nei trattati di commercio. Roma: Cooperativa poligrafica editrice.

Mariani, J. F. (2011). How Italian Food Conquered the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mendelson, R. (2009). From Demon to Darling. A Legal History of Wine in America. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California.

Milani, E.R. (1993). “Peonage at Sunnyside and the Reaction of the Italian Government”. In Whayne, J.M. and Jeannine. M. (eds.). Shadows over Sunnyside, an Arkansas Plantation in Transition, 1840-1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press: 39-49.

Mocarelli, L. (2013). “The long struggle for the Chianti Denomination. Quality versus Quantity”. In Ceccarelli, G., Grandi, A. and Magagnoli, S. (eds.). Typicality in History. Tradition, Innovation and Terroir. La typicité dans l’histoire. Tradition, innovation et terroir. Brussels: Peter Lang, 323-340.

Monti, A. (2000). “Le politiche nazionali agricole dal 1900 al 1945”. In L’Italia agricola nel XX secolo. Storia e scenari. Roma: Donzelli, 518-523.

Official Catalogue of Exhibitors. (1904). Universal Exposition. St. Louis: Committee on Press and Publicity, by the Official Catalogue Company: 247-250.

Ottavi, E. and Marescalchi, A. (1897). Vademecum del commerciante di uve e di vini in Italia. Casale: tip. Carlo Cassone.

Paul, H.W. (2002). Science, Vine and Wine in Modern France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pedrocco, G. (1993). “Un caso e un modello: viticoltura e industria enologica”. In D’Attore, P.P. and De Bernardi, A. (eds.). Studi sull’agricoltura italiana: società rurale e modernizzazione. Milano: Feltrinelli, 315-342.

Phillips, R. (2016). French Wine. A History. Oakland: University of California Press.

Piazza, M. and Bellanda, A. (2014). Manifesti Posters. Mangiare &bere nelle pubblicità italiana 1890-1970. Milano: Silvana editrice.

Pinney, T. (1989). A History of Wine in American: from the Beginnings to Prohibition. Berkely: University California Press.

Pollice, F., Albanese, V., Urso, G. and Epifani, F. (2015). “Vineland. Il contributo degli italiani alla costruzione dei paesaggi vitivinicoli nordamericani”. In Cristaldi, F. and Licata, D. (eds.). Nel solco degli emigranti. I vitigni italiani alla conquista del mondo. Milano: Bruno Mondadori, 121-135.

Roccas, M. (2003). “Le esportazioni nell’economia italiana”. In Ciocca, P. and Toniolo, G. (eds.). Storia economica d’Italia. 3. Industrie, mercati, istituzioni. 2. I vincoli e le opportunità. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 37-135.

Rosano, D. (2000). Wine Heritage. The Story of Italian American Vintners. San Francisco: Wine Appreciation Guild, 30-31.

Rossati, G. (1900). Relazione di un viaggio d’istruzione negli Stati Uniti d’America. Roma: Tip. Nazionale di G. Bertero.

___, (1888). Descriptive Account of the Wine Industry of Italy. Roma: Società generale dei viticoltori italiani.

Rossiter, J. (1898). A history of the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, by authority of the board of directors. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Rosso, M. (2009). Barolo. Mito di Langa. Torino: Omega edizioni.

Rumbarger, J.J. (1989). Profits, Power, and Prohibition: American Alcohol Reform and the Industrializing of America 1800-1930. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ruvoli, J. (2010). “An Agricultural Colony in Alabama: Hull House and the Chicago Italians”. In Barone, D. and Luconi, S. (eds.). Small Town, Big Cities: the Urban Experience of Italian Americans. New York: American Italian Historical Association, 146-164.

Sassatelli, R. (2017). Consumer Culture. History, Theory and Politics. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Segers, Y., Bieleman, J. and Buyst, E. (2009). Exploring the food chain. Food production and food processing in Western Europe, 1850-1990. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.

Simpson, J. (2011). Creating Wine. The Emergence of a World Industry 1840-1914. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Teughels, N. and Scholliers, P. (2015). A Taste of Progress. Foodat International and World Exhibitions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Ashgate.

Thompson, P.B. (2014). “Thomas Jefferson’s Land Ethics”. In Holowchak, M.A. (ed.). Thomas Jefferson and Philosophy. Essays on the Philosophical Cast of Jefferson’s. Lanham: Lexington Books, 61-78.

Trentin, P. (1895). Manuale del negoziante di vini italiani nell’Argentina. Buenos Aires: Tip. Elzeviriana di P. Tonini.

Unwin, T. (1991). Wine and the Vine. An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade. London-New York: Routledge.

Vaquero Piñeiro, M. (2018). “La nascita delle cantine industriali in Italia”. In Ciuffetti, A. and Parisi, R. (eds.). Paesaggi italiani dellaprotoindustria. Roma: Carocci, 205-216.

___, (2015). “Readings for Farmers: Agrarian Almanacs in Italy (Eighteenth-Twentieth centuries)”. The agricultural history review 63(2): 243-264.

Vezzosi, E. (2012). “Gli Stati Uniti del primo Novecento: il progressismo, l’impero e le loro contraddizioni”. In Fiorentino, D. and Sanfilippo, M. (eds.). Stati Uniti e Italia nel nuovo scenario internazionale 1898-1918. Roma:

Gangemi, 50-75. Walker, L. (2005). The Wines of the Napa Valley. London: Mitchell Beazley.

Weekly Bullettin of Italian Chambers of Commerce of New York. (1919). XX, 2.

World’s Columbian exposition. (1893). Official catalogue, vol. 1. Agriculture building and dairy building. Chicago: W.B. Gonkey Company.

Recibido: 23-10-2017 Aprobado: 30-04-2018