Gaspar Martins Pereira y Amándio Moráis Barros.

"Port Wine and the Douro Región in the Early Modern Period" / 'El vino de Porto y la Región del Douro en la Época Moderna"/ "O vinho do Porto e a Regiao do Douro na Época Moderna".

RIVAR Vol. 3, N° 8, ISSN 0719-4994, IDEA-USACH, Santiago de Chile, mayo 2016, pp. 110-144

Port Wine and the Douro Región in the Early Modern Period

El vino de Porto y la Región del Douro en la Época Moderna

O vinho do Porto e a Regiao do Douro na Época Moderna

Gaspar Martins Pereira* Amándio Morais Barros**

Profesor catedrático del Departamento de História y Estudios Políticos e Internacionales de la Facultad de Letras de la Universidade do Porto. Investigador de CITCEM -Centro de Investigagao Transdisciplinar Cultura, Espago e Memória. Correo electrónico: gasparmp@sapo.pt

Profesor de la Escuela Superior de Educación del Instituto Politécnico de Porto. Investigador de CITCEM -Centro de Investigagao Transdisciplinar Cultura, Espago e Memória. Correo electrónico: amandiobarros@hotmail.com

Abstract

This paper will focus on the analysis of the Port wine dynamics in the Early Modern Period. One of the major objectives we'll try to achieve is to present evidence that the birth of Port wine was the result of a long and persistent process of implantation in the territory in which men took advantage of favourable natural conditions of the ground to manufacture a wine which is unique. The first section will deal with the relation between wine and its implantation in the territory in which we will prove that Port wine can only be identified with the Douro region in the 18th century although the exploratory phase begun in the Middle Ages. Next, we will focus on the historical roots of wine-growth in the region by presenting evidence from chroniclers and archive documents that some parts of the region (namely Lamego) had already been involved in the commercialization of wines of quality ("old" and "aromatic" wines) at an international level. The third section deals with the role attributed to the soil on the wine production which is a subject that leads us towards the role of the Company (the Monopolistic Company founded by Pombal in 1756) in the protection of the Port wine quality by an innovative process of demarcation which made the Douro region the first formally demarcated wine region in the world. The fourth chapter will deal with the historical emergence of the Douro/Port wine and the role played by the local elites in the creation of a brand; from the Port wine case, it is clear that the wine production (and the recognition of the brand Port) was the result of an economic strategy designed early in the Middle Ages by the Cistercian convents in the region, which was followed by the merchant elites of Porto which dominated the wine distribution. From this point of view, it is interesting to analyse the process by which some of the proprietors of "wine farms" intended (and in many cases achieved) to obtain the statute of "Porto neighbours" which granted them with trade and commercial privileges. In the following and final section we will meet the exporters, merchants, nobility (and nobility-merchants) and convents, the bet they place in the wine exportations to England and, later, the appearance of the Company's shareholders, the novel Port wine elite that transformed business and the city into an huge and significant enterprise.

Keywords: Port wine, Douro Region, economic and social history.

Resumen

En este trabajo se analiza la dinámica del vino de Oporto en la Edad Moderna. Se explica que la creación del vino de Oporto es resultado de un largo y persistente proceso de implantación de la vid en un territorio donde los hombres se aprovecharon de las condiciones naturales favorables para la fabricación de un vino único. En la primera sección, el artículo habla de la relación entre el vino y su implantación en el territorio; se demuestra que el vino de Oporto solamente se puede identificar con la región del Duero en el siglo XVIII, aunque la fase exploratoria empezó en un tiempo tan temprano como la Edad Media. A continuación se estudian los orígenes históricos del crecimiento del vino en la región mediante la presentación de textos de los cronistas medievales y modernos, además de documentos de archivo que prueban que partes del territorio, como la región alrededor de Lamego, se encontraban ya profundamente involucradas en la comercialización de vinos de calidad (de "vinos viejos y aromáticos") a nivel internacional. La tercera sección desarrolla la conexión entre la tierra y la producción de vino, tema que remite para el papel de la Compañía Monopolística fundada por Pombal en 1756 en la protección de la calidad del vino de Oporto por un innovador proceso de demarcación que permitió que la región del Duero fuera la primera región vinícola demarcada y reglamentada en el mundo. En la cuarta parte se estudia la aparición histórica del Duero / vino de Oporto en relación a la actuación de las élites locales en la creación de una marca; en el caso del Vino de Oporto queda claro que la producción de vino (y el reconocimiento de la marca Porto/Port Wine) fue el resultado de una estrategia económica diseñada a principios de la Edad Media por los conventos cistercienses en la región, que fue seguido por las elites comerciales de Oporto que dominaron la distribución de vinos. Desde este punto de vista, es interesante analizar el proceso por el que algunos de los propietarios de "granjas de vino" intentaron (y en muchos casos lograron) conseguir el estatuto de "vecinos de Oporto", logrando privilegios comerciales. En la siguiente y última sección se desarrolla el análisis de los exportadores, comerciantes, nobleza (y nobles-comerciantes) y monasterios, la apuesta que depositaron en las exportaciones de vino hacia Inglaterra y, más tarde, la aparición de accionistas de la Compañía, la élite del vino que logró transformar los negocios locales en una amplia y significativa empresa.

Palabras clave: vino de Oporto, Duero, historia económica y social.

Resumo

Neste trabalho analisamos a dinámica do vinho do Porto na Época Moderna, tentando fundamentar a ideia de que a criagao deste vinho é o resultado de um longo e persistente processo de implantagao da vinha num território em que os homens aproveitaram as condigóes naturais favoráveis para a produgao de um vinho único. Na primeira secgao, referimo-nos á relagao entre o vinho e sua implantagao no território, procurando demonstrar que, embora o vinho do Porto só se identifique com a regiao do Douro a partir do século XVIII, a fase exploratória terá comegado muito antes, durante a Idade Média. No ponto seguinte, estudamos as raízes históricas do desenvolvimento da viticultura na regiao, partindo de textos de cronistas medievais e modernos, bem como de documentos de arquivo, que provam que algumas partes do território, como a regiao em redor de Lamego, estavam já profundamente envolvidas na comercializagao de vinhos de qualidade (de "vinhos velhos e aromáticos") a nível internacional. A terceira secgao aborda a relagao entre a terra e a produgao do vinho, tema que remete para o papel da Companhia monopolista fundada por Pombal em 1756 na protecgao da qualidade do vinho do Porto por um inovador processo de demarcagao que fez do Douro a primeira regiao vinícola demarcada e regulamentada do mundo. Na quarta parte, estudamos a emergencia histórica do vinho do Porto/Douro e o papel desempenhado pelas elites locais na criagao de uma marca regional; no caso do vinho do Porto, torna-se evidente que a produgao de vinho (e o reconhecimento da marca Porto) foi o resultado de uma estratégia económica desenhada desde cedo, a partir da Idade Média, pelos conventos cistercienses da regiao e seguida pelas elites mercantis do Porto que dominaram a distribuigao desses vinhos. Deste ponto de vista, é interessante analisar o processo pelo qual alguns propietários de "granjas de vinho" tentaram (e em muitos casos conseguiram) alcangar o estatuto de "vizinhos do Porto", obtendo privilégios comerciais. Na seguinte e última secgao, procuramos analisar os exportadores, comerciantes, nobres (e nobres-comerciantes) e mosteiros, a aposta que fizeram nas exportagóes de vinho para Inglaterra, e, mais tarde, os accionistas da Companhia, a elite do vinho que transformou os negócios locais numa ampla e significativa empresa.

Palavras-chave: vinho do Porto, Douro, história económica e social.

Introduction

This study examines the socio-territorial dynamics of fortified wines of the Douro in the Modern Era, when the confluence of conditions enabled the emergence of a type of wine with unique features and its recognition in the market under the name "Port wine". We will seek to demonstrate that Port wine, as we know it, is the result of a long, persistent and complex process rooted in its home territory, in articulation with more or less distant markets. In this process, Man soon recognised and explored the advantages that the land provided him, offering him favourable conditions—hillside vineyards, low yielding and difficult to work, but benefitting from an exceptional climate and a productive suitability of the land—to obtain high-quality wines, with excellent aroma and flavour, and likely to have a long life.

In this text, we will seek to understand:

i) the relationship between the production of fortified wines of the Douro and the recognition of the specificity of its land of origin, as well as the historical roots of this juxtaposition;

ii) the historical conditions of Douro wines and their meaning;

iii) the issue of the soil and the importance given to it in the production of unique wines;

iv) the role of regional elites in the creation and consolidation of the "Port" brand;

v) how Port wine became a vehicle for social prestige, and how it was used by regional elites for self-promotion, as well as the efforts made by these elites in order to maintain control of production and the conditions for the marketing of the product.

The Douro and Port wine: historical roots of a strained relationship

The best Douro wines were already highly valued at least since the late Middle Ages, fetching prices much higher than current wines. A writer from that period, Rui Fernandes, overseer of the King in Lamego, gave us an overview of the production in the Douro area. Written in 1531-1532, in a period of transition from medieval to modern times, the description made by Rui Fernandes abounds in details on the wealth and quality of production. It shows us a diversity of vineyards, but which are mostly found on the slopes of the Douro, producing aromatic wines with aging capacity, served in the Royal Court and in manor houses. Fernandes provided data on evidence of abundant production, according to standards of that time (about 15 thousand barrels every year for this part of the Douro), and on its export capacity, for both the domestic (Entre Douro e Minho, Aveiro and Lisbon) and external markets (for the Royal Court and manor houses of Castile) (Fernandes, [15311532] 2001: 34-42).

By that time, the best Douro wines, although recognised in regional and inter-regional markets (domestic and abroad) as "wonderful vinhos de pé" and "aromatic" wines, were still far from achieving the export vocation which would give them the designation of "Port wines", but they had undoubtedly a commercial vocation, appearing in various 16th century documents under the designation "vinhos de carregagao" (Barros, [1548] 1919), which in regional terminology meant wines that were intended to be shipped along the river to Porto.

The most common names that appear in medieval and early modern era documents—"Riba Douro", "Cima do Douro", "Lamego" wines, etc.—leave no doubts as to the fact that the geography of the winegrowing lands, in those times, just barely coincide with the boundaries of the país vinhateiro [wine country] as defined by the 18th century boundaries.

On the other hand, settlement in the region, characterised by manorial (noble and monastic) and municipal (rural and urban) structures inherited from the Middle Ages, had an undeniable influence on the production map of the territory, imposing extensive "empty" spaces1 that would only be occupied and exploited in later times.2

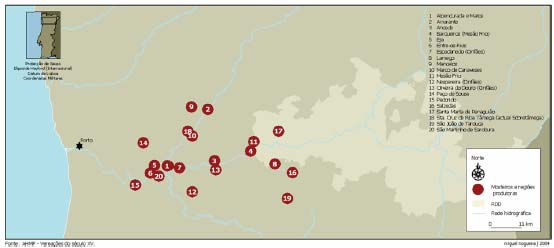

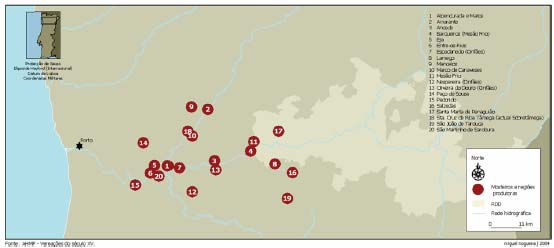

Based on the 15th-century Porto Vereagoes (Council reports) with references to the arrival of wines in the town, we obtain the following cartographic representation.

Wines in the Middle Ages. Monasteries and producing regions in "Riba Douro"

Reference: AHMP, Vereagoes do século XV

As can be seen, the major centres supplying wine to the city coincide with the most populated nuclei along the lower courses of the Douro and Támega rivers, roughly between Entre-os-Rios and Amarante. This is explained by the concentration of people and properties traditionally involved in winegrowing, in the valleys designed by the great river and its tributaries, as well as the ease of transport (Douro at its best navigation stage) on barges, which ensured a heavy traffic that had the city as its main reference. In the area of the current regido demarcada [demarcated region], the wines produced in Santa Marta de Penaguiáo and Lamego stand out, which is precisely the most intensive production area, and which was to benefit the most from the wine region's demarcations in the mid-18th century. In the area of Lamego, we should mention the wines from Varosa valley, shipped since the time of the Cistercian monasteries in Salzedas and S. Joáo de Tarouca, with an investment in viticulture since the 12th century that contributed decisively to regional specialisation.3

This general panorama was set to be the case for some time. In another moment, in 1585, a well-documented year regarding the entry of wines in Porto, with a view to supplying the armadas organised at that time, the place of birth of the boatmen in charge of transport reveals that continuity.4

Number of barréis transported to Porto between January and February 1585 according to the placeof origin of the boatmen

Reference: AHMP. Vereagoes, liv. 27

The expansion of the Douro winegrowing area from the 17th century coincided with the rapid market growth, especially the British one. The export vocation of Douro fortified wines, from Porto, already present in the 16th century with the demand for maritime and overseas transport, gained strength since the late 17th century, increasingly to the prime destination of the UK market. In a few decades, Port wine would become "the Englishman's wine",5 which had a twofold consequence: the rapid development of regional production and the manufacture of more fortified, sweet, aromatic and deep-purple fortified wines, suited to the British taste. The Alto Douro region, where one could obtain wines with those characteristics, strengthened, at the same time, its wine vocation. And the names "Cima Douro wines", "Port wines" or "vinhos de feitoria" became synonymous.

This was the panorama with which the Prime-minister of King José I, Sebastiáo José de Carvalho e Melo, future Marquis of Pombal, would be faced in the mid-18th century, at a time when the Porto wine trade suffered a serious crisis. It should be pointed out that Port wine was, at that time, by far the most important Portuguese export product, colonial products excluded. This status explained why wine was seen by the absolutist state as a strategic product that should be safeguarded, in Pombal's mercantilist perspective. The solution adopted was the creation of a Company—the Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro—, by royal charter of 10 September 1756, with a royal charter to demarcate the producing region and control wine production, transport and trade. Under Pombal's strict and complex laws, "port wine" or "de feitoria", with prices established by law, became an "exclusive" production of the demarcated area of Alto Douro.

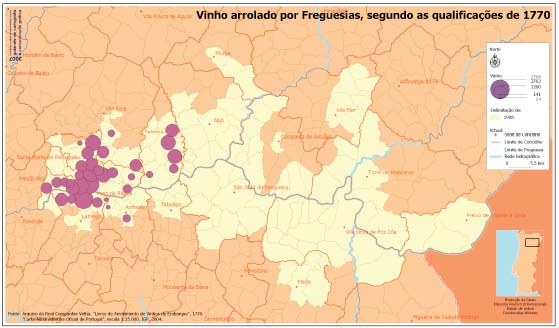

Production of "vinho de feitoria" (Port wine) in the Douro region in 1770

Reference: Arquivo da Real Companhia Velha, "Livros de Arrolamento de Vinhos de Embarque", 1770. Carta Administrativa Oficina de Portugal, escala 1:25.000, IGP, 2004

Historical conditions of the advancement of Douro fortified wines

The promotion of Douro fortified wines in the Modern Era stemmed mainly from its mercantile vocation. The early recognition of its quality by the markets—Porto, Iberian, overseas and British, in this order—determined not only continued investment in regional production but also the improvement of wine-making techniques and the adaptability of wines to consumer markets.

It should be noted that in early modern times, Douro wines, whether assembled with other Portuguese regions, or not, responded primarily to domestic consumption needs and to the logistics of the armadas. Although it was exported (apart from Castile, there are reports that since the Middle Ages consignments of wine were transported on Portuguese ships to England and Flanders), it was not significan! Wines were generally a part of other merchandise (salt, hides, fish, and as the modern period progressed, pastel, colourings and sugar from the Atlantic region) typically sent on Portuguese ships that sought the European ports in the 15th and 16th centuries. We should also note that, at the time, these wines could not compete in any way with French wines (Pereira; Barros, 2013: 198-199).

The boost given by the armadas—sent every year to India, Brazil and the rest of the Atlantic area—helped spread the area of influence of wine. This process took place between the 16th and 17th centuries. Then, throughout the 17th century, the pressure exerted by the Dutch demand (on the process of building an overseas empire in need of wines and in a context of rivalry with France, a traditional supplier, in particular with the protectionist policies of Colbert) in the main European wine regions, ultimately changed the international wine trade substantially. We owe to the Dutch and the innovations they introduced in the production of fortified wines, balanced with spirits and fit to travel long distances, the "wine revolution" that marked the history of many European wines in the 17th century (Enjalbert, 1953: 322). In the case of fine wines from the Douro, between the early 17th century and early 18th century, this "revolution" led to decisive technological changes: first, in the warehouses of Porto and Gaia traders, with the addition of spirits to already prepared wines intended for export, thus obtaining stronger wines with a higher alcohol content; then, in the early 18th century, with the addition of spirits to the must, in the wine-cellars of producers in the Douro, to stop fermentation and preserve the natural sweetness of grapes (Pereira; Barros, 2013: 202-206). These changes—basically, this adaptation to market tastes—were stimulated by the increasing demand for fortified Douro wines by the British market between late 1670s and 1720s, in an environment favourable to Iberian wines, created by rivalries and wars between the Northern maritime empires.

Land, where it all begins

We can say that from very early on the issue of soil and natural conditions that favoured the production of wines with peculiar features attracted the attention of the Douro wine farmers. Indeed, empirically, traditional Douro wine-making preferred poorer schist soils, sometimes on very steep slopes, with better sun exposure for the perfect maturation of grapes, avoiding the humid areas, left for vegetable gardens and other crops, and the higher ground, left for the forests.

It is obvious that in a poor region, the geography of the vineyards often clashed with the survival needs of local people, in an economy of consumption that could not do without "lands of bread" and livestock raising, at least in the case of small growers who were (and still are) the overwhelming majority (always over 90%). This relation between subsistence farming and the commercial vocation of Douro wines in fact determined the adoption of organisational forms of farming land and wine-making techniques, which left evident traces in the Douro landscape. In some areas where it was possible to combine vineyards with grain cultivation, as shown by the author of Memória, of the late 18th century, the vineyard was formed only by vines planted em pilheiros, on the wall of the terrace, leaving the in-between land called geio, free for cultivating cereals (Fonseca, 1791: 67).

On the other hand, the strong differences in the wine region due to topography and the composition of soils, from the geological point of view, with different types of schist, and in some areas granitic eruptions, and even the more or less gravelled areas, determined a wide variety of vineyard "terroirs", the potential of which was recognised for the production of a specific type of wines. Thus, some areas of the Varosa and Pinháo river valleys were known, prior to the Company, for the excellence of their white wines, and others were known for their deep-purple wines (Covas do Douro, for example). As is still the case today, despite recent technological modernisation, the Douro region has remained intransigent regarding a single type of wine. This also explains the persistence of a vast range of wines with specific features that are the result of their place of origin (sometimes a small farm) and of the grape varieties used and the vinification process and ageing.

This awareness of the diversity of Douro wine terroirs explains the differentiation between vine plots since the first demarcation of the region in 1758. On a charter dated 30 November of that year, the Curator of the Company informed Minister Sebastiáo José de Carvalho e Melo about the difficulties posed by the demarcation, taking into account the diverse conditions of soil and climate, sometimes within the same parish: "dentro dum mesmo limite se produzem vinhos bons e vinhos ruins, conforme a situagáo do terreno, mais ou menos alto, e dos ventos que o dominam e sol que o rega" [within the same area, we find both good and bad wines, depending on the lower or higher grounds, and on the winds and sun] (Cit. in Fonseca, 1950: 21-22).

It is the awareness of this diversity that continues to govern, even today, the classification of the Douro vineyards, and the awarding of higher or lower scores for the "benefit" that allows farmers to use their grapes in the production of more or less qualified Port wine. The "scoring method" defined by Alvaro Moreira da Fonseca, used since the 1940s, indeed combines a set of criteria according to regional tradition—productivity, climate (altitude, location, exposure and shelter), ground (nature of the terrain, slope and gravel), and cultural conditions (grave varieties, cultural features, age of the vineyard and spacing)—that define the category of each vineyard lot (from A to F) of the Demarcated Region of Douro (Fonseca, 1949).

Regional elites and the "Port" brand

In a long-term perspective, since the Middle Ages the expansion of the Douro vineyards is, at first, a hesitant process. It was difficult for wine to have an advantage over cereals, because bread has priority over all else. But there is a real progression. The advance of vineyards is due largely to monasteries, dynamic hubs of settlement and economic transformation. In the case of Douro, which concerns us here, this movement is evident in the case of the Cistercian abbeys, responsible for an unprecedented increase of viticulture, in both quantity and quality—a model that they had already experimented successfully in France and Germany. Similar to what had happened in those European regions, in Portugal only the great religious institutions had sufficient resources to match the large investment required—especially in terms of work and skilled and intensive labour—in planting and growing vineyards. With the donations, legacies, exchanges and acquisitions, the ecclesiastic houses (the local churches and Cistercian monks were followed, at a distance, by the Franciscans, Benedictines and later, and quite clearly, the Jesuits and Oratorians) built important heritage in the region, enhanced through the promotion of experiments in viticulture, decisive for both consumption and commercialization. This process is quite noticeable in the Douro, again since the Middle Ages, in its relation with the city of Porto, and is accentuated in the Modern Age when the wines produced were gradually intended firstly for urban consumption, and then to supply the armadas, the reference markets and the overseas territories.

In the wake of Portuguese trade, evident in the 14th century and confirmed in the two centuries that followed, wine played an interesting role as support to business conducted increasingly by sea, in medium and long distances.

This, as one would expect, implied the growth of production. It was not enough to feed the needs of the local markets, and particularly the cities. In addition to urban consumption, there were other types of demands: first and foremost, the demand of merchants interested in obtaining wine to sell in far-off places, provided the wine could stand the journey and reach the buyers overseas and in Europe in a good state, and then the demand from ship-owners and shipping agents, who needed wine to supply their ships.

The religious houses that joined this economic project (e.g., the Cistercians, as stated) staged forms of heritage organisation and management and technology breakthroughs. The first large wine-producing farms emerged as a result of their initiative, fitted with wine presses, barrels and cellars, where wine was produced and preserved6: e.g., Folgosa (nowadays Quinta dos Frades), Pago de Monsul and Mosteiró, cited by Rui Fernandes in the 16th century and still existing today. The monastery of S. Joáo de Tarouca owned transport barges that sailed the Douro to Porto, bringing wine and taking salt, as was the case of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Salzedas. Other monasteries downstream, such as Alpendurada and Santa Clara, or the church of Eja, shared the toll at Entre-os-Rios and the profits of the transit of wine. Santo André de Ancede, in Baiáo, owned vineyards in Penaguiáo and Mesáo Frio. This caused a tendency to draw nearer to the city of Porto, aiming for the sometimes not so peaceful status of neighbour of Porto, a city that facilitated the trade of wine, both within and outside the borough.7

At that time, alongside the monks came new investors. Since the 15th century, the bourgeoisie, based in the city, took interesting steps in an attempt to acquire wine farms. New landlords appeared in Porto, which is the most documented case, but also in inland centres, such as Lamego and Viseu, and new production units were formed (many of them, oddly enough, formed from plots of land owned by the church that were once leased as casais) that interfered in both the change of production processes and in the business schemes that marked the life of the product, making it a profitable business, as part of larger commercial networks and circuits.8

As the city became involved in other businesses at a worldwide economy scale, these mercantile elites joined the old urban aristocracy. In the second half of the 14th century, these mercantile elites, dominated by New Christian businessmen, had interests in various parts of the territory associated to the production of quality wines9, but also other tradable products, such as sumac, massively exported to the dyer markets of Northern Europe. Although they had knowledge of property ownership, they preferred the fruition of a business benefice, creating ephemeral business companies (but consecutively renewed) that combined capital (from the city) and labour (by the local staff),10 in a model of exploitation of potentially marketable productive wealth, typical of the Ancien Regime.

While the clergy members had the material means and the techniques to promote the development of wine making, and the urban aristocracy benefitted from old social and economic models to organise domains and exploit the land, the merchants used their ability to intervene in the most favourable trade and financial markets to bring about the consistent affirmation of the region.

Monks, nobles and merchants. The builders of modern Douro. The Douro of wines, of sumac and olive oil, with productions stimulated for business purposes. We should retain these general ideas, since our current knowledge does not allow us to determine the weight each one has in the wine sector, or the value of productions that were marketed.

The organisation of armadas, a recurrent phenomenon in Portugal in the 15th and 16th centuries, triggered many requests on the economy of seaports, of their umlands and hinterlands, which would be reflected on the production of wines, which were essential to ships and national communities which, from then on settled in the discovered and conquered lands. This is a phenomenon of rupture. A phenomenon that has nothing to do with medieval tradition, local consumption, or short distance trade. This is the Iberian reality, the Iberian expansion and the intercontinental routes it opened. Symbolically, we can establish as a starting point for this new reality the request made to the Porto Council in 1502 by Afonso Leitáo, contractor of a ship from India, for large quantities of wine that could be found in the city to supply his ship on the eve of his departure to the East. The Council turned him down. And would again and again turn down similar requests. The fact is that port and urban authorities still had a medieval mind of self-sufficiency and protectionism, and were not ready to assimilate this openness to world trade. But they would adapt quickly. Soon, the typical image of the ports would show rows of barrels lined up on the docks waiting for shipment. Even in Porto, the cooperage became the engine of transformation of the most important riverside neighbourhood: Miragaia.11

As we move forward in the 17th century, a clear merchant aristocracy/bourgeoisie is defined in Porto, with interests in the Douro wine business and often with land interests or nurturing strategic alliances with major producers in the wine region.

Value, prestige and power

The development of the Douro wine business strengthened the relations between the merchant town and the producing region. We have already seen how since the 14th century, many Porto "neighbours" owned vineyards and farms in the Douro region, and had their wines brought from there for private consumption or to sell. Throughout the 17th century, the wine business seemed to have strengthened the power of the bourgeois elite, established in the municipal administration, which was linked to the Douro wine landlords, who sometimes also lived in the city. Moreover, in the first half of the 17th century, the role of producers was still essential in the marketing of their wines. Between 1620 and 1640, the largest number of declared wine producers in Porto lived in the Douro, and in the same period, the Douro population represented about a third of the exporters.

The articulation between the Douro and Porto, the natural market for Douro wines and an exporting centre, was not always peaceful. Since the Middle Ages, the city had always tried to control its commerce and benefit from its taxes. Throughout the 15th century, if not before, the tax burden on wines was the city's largest source of income.12 But the attempts to increase the tax burden on Douro wine by the City Council of Porto often came up against the joint opposition of the inhabitants of Porto and the wine producers of Cima Douro, as in 1647-1648, according to Aurélio de Oliveira. The conflict was resolved only by royal intervention, determining that the Council could not impose new taxes on the wine (Oliveira, 1984: 229).

The growth of the exporting business, visible since the late 17th century, attracted new players, Flemish, Hamburg and especially English merchants, reinforcing the concentration of capital and new investments in storage and marketing in Porto and Gaia. It is not difficult to understand the growing primacy of whoever organised the business and dominated the commercial network, upstream and downstream, maintaining, on the one hand, privileged relationships with the largest Douro producers, and on the other hand, weaving a network among the merchants of the product's ports of destination. At a time when Port wine gained market recognition, the trend seems to have been the growing appropriation by the marketing sector of the advantages of the designation "Port". The "aristocracy of Port wine" dominated the city exporting the wine and dominated the producing region, but not without conflicts caused generally by the struggle for the control of the name "Port", prices and distribution chain. The relations of complementarity and balance between the interests of the producer and the commercial sector were therefore driven further and further apart. In 1754, the Douro farmers accused the British merchants of Porto of "wanting to make the business theirs, not involving any of the producers".13

The commercial crisis of the mid-18th century led, as we have seen, to the intervention of the state and to the imposition of a structure to control the producing region and the trade of its wines. At the time, pressed by the interests of the major Douro wine growers and by the Porto merchants, the measures adopted by Pombal's government aimed to stop the British from dominating the sector. But, above all, as Borges de Macedo noted, it was the rationale of absolutist governance, to control a key sector of the national economy and to preserve —and, at the same time, subordinate—the interests of dominating social groups associated to them (Macedo, 1982: 51).14 In this sense, at a time when the conflict of interests heightened between the productive sector and the commercial sector, the State sought to assure the major Douro wine farmers part of the capital gains arising from the reputation achieved by Port wine in the foreign market,15 but without questioning the very strong interests at stake in the export sector.

Conclusions

There is an historical process in which wine, and wine production, identifies with the Douro region. Largely due to the human occupation of the territory and the restrictions posed by the soil and accessibilities, until the 17th century, the winegrowing area barely coincided with the boundaries of the current demarcated region. However, the wine produced there soon showed a strong tradability, provided by its aging capacity, honoured in the descriptions from the late Middle Ages. From the 17th century on, with increasing foreign demand, and in particular, the specific demand of the English market, the winegrowing land expanded within the Alto Douro region, where the wine could be produced according to the characteristics desired by the English, who had become its main buyers: fortified, sweet, aromatic and deep-purple. The Pombaline demarcation of the 18th century crystallised this wine reality.

Throughout the centuries, wine has benefitted from external stimuli to the region and to local consumption, to develop and be enhanced, such that it achieved a prestigious position in international markets. In the Medieval period, the production satisfied, almost exclusively, local consumption and the city of Porto, but in the 16th century, Douro wine ensured the supply of the armadas and gained an economic dimension that attracted the attention of merchants. From the 17th century, the sector was largely stimulated by the "wine revolution" carried out by the Dutch (in the fortification of wines) and generalised in the 18th century, in the warehouses of Porto/Gaia and in the cellars in the Douro region, to meet the demands of the UK market.

The Douro region has provided the necessary conditions for making a special wine. If initially the wine had to share the land with cereals and livestock (even inventing unique solutions for the plantation of vines, for e.g., the pilheiros), as it became an important capital gain, wine began to dominate the landscape and became more diverse according to its attributes. The 18th century marks the awareness that the wine produced varied in quality, depending on various factors, such as climate, soil and state of the vineyards. Therefore, the Pombaline demarcations established the classification of the vineyards according to the different types of wines (and different legal prices) that those vineyards were authorized to produce. In the 20th century, these factors resulted in a scoring method which is still used today to classify the vineyards.

The establishment of the vineyard and the development of the Douro wine trade were the result of group interests that, according to the contexts, were part of the social and economic processes in which wine played the key role. Initially, Douro wine, like other great wines of Europe, was the work of monasteries, the work of Cistercian monks, owners of fine land and persistent instigators of toiling the land. However, early on, the wine business drew the interest of the merchant elites of the city where it was sold and from where it was exported. In Porto, a trade hub with a maritime, Atlantic vocation, the Douro wine trade was a profitable business for the merchants who prepared the ships and participated in the construction of world economies in the 16th and 17th centuries. As these traits develop, we see a rising elite with strong interests in the Douro, trading in wines and sumac, and also investing in properties and becoming linked to the destinies of the major producers of the wine region. This process was already consolidated in the 18th century.

The strengthening of relations between the producing region, the Douro, and the exporting centre, Porto, were historically and structurally inevitable. The medieval displacement of land-owning abbots towards the city, thus obtaining the status of "neighbours", was the first step in a relationship that deepened over time. Not without there being an attempt of a process, often accomplished, of urban dominance over the wine country, with the outburst of more or less heated conflicts, requiring the intervention of the central power.

Having become an exporting business, the wealth of an economy increasingly dependent on outside interests, the wine business, like others, attracted new foreign players, Flemish, Hamburg and especially British, who took part in a struggle to control the name "Port" and the decisions over the wine business. Whereas the absolutist State, through Pombal and the Company he created, tried and, to some extent, managed to safeguard the interests of the great Douro wine producers, there was little or nothing that it could or wanted to do about the exporting interests of the foreign elites of Port wine, given the strong dependence of the Port wine sector on international markets.

Notes

1 A reality that can be explained both by the low productivity of the land and by a morphology that made it difficult to work due to the poor accessibility.

2 We need further studies that allow us to establish lines of continuity of settlement and the profile of the Douro communities, already shown in the povoas formed in the early Middle Ages.

3 Even though these monasteries owned estates in different areas.

4 Although we are talking about transport, it does not mean that the origin of the wine is not different. However, other references in documents—municipalities and notaries—continue to report the same production maps.

5 See, for example, Bradford, 1969. The expression is often used by various british authors.

6 Vinhos moles (often interpreted as must wines), cozidos ("cooked" wines), garavatados (a certain quality of green wine), pintados (tinted wines), limpos (clean wines), among others, as cited in the documents.

7 The neighbours did away with barriers between municipalities in the sale of wine and would export freely most of the production (Ventura, 1998: 89-93; Duarte; Barros, 1997: 77-118).

8 It is common to see Porto council members (the first landowners emerging from this urban movement) on the eve of the harvest to ask to be excused from the council meetings, heading to Riba-Douro, Lamego and other closer locations to "harvest" their vineyards.

9 For example, in Tourais, Canelas or Rede.

10 But this is not the only case. We should also note the many partnerships established for the exploitation of wines—proving the interest that they had, in the 16th century, for the town's business—among capitalists and the town's merchants; the former, invested the start-up capital and the latter invested their "labour and skills". The profits, as in the cases referred to, were split equally between the two investors.

11 Municipal Historical Archive of Porto. Livro 1° de Próprias, fls. 250 and 270, specially Vereagoes, liv. 16, fls. 51v-52. These documents are cited and analysed in Barros, 2004: 251-252, 264-265.

12 And they would continue to have an important weight in the finances of the borough, even when Brazilian sugar dominated the business panorama.

13 Resposta dos Comissários Veteranos as Novas Instrugoes da Feitoria, 1754. Established in 1727 in Porto, the Factory House represented the interests of the British merchants in the city. At the height of the commercial crisis of the mid-18th century, the combination of these interests against the interests of the Douro farmers was visible in the assuming of group positions: see Novas Instrugoes da Feitoria Inglesa a respeito dos Vinhos do Douro, 1754. Doth documents are transcribed in full in Tenreiro, 1944: 76-82. On the growing dominance of the Douro wine business by the English, see Cardoso, 2003.

14 According to the author, "The rule of Pombal intervenes in defense of the traditional producer against new competitors encouraged by the Methuen Treaty to produce, and the existence of colonial sources of consumption".

15 This is a goal common to all regions of designation of origin. See, for example, Unwin, 1991: 312-313.

Bibliography

Barros, Amándio. Porto: a construgáo de um espago marítimo nos alvores dos tempos modernos. Vol. I. Porto, Faculdade de Letras, 2004.

Barros, Joáo de. Geografia de Entre Douro e Minho e Trás-os-Montes [1548]. Porto, Cámara Municipal do Porto, 1919.

Bradford, Sarah. The Englishman's Wine. The Story of Port. London, MacMillan, 1969.

Cardoso, António M. Barros. Baco & Hermes. O Porto e o comercio interno e externo dos vinhos do Douro (1700-1756). 2 vols. Porto, Grupo de Estudos de História da Viticultura Duriense e do Vinho do Porto, 2003.

Duarte, Luís Miguel y Amándio Barros. "Coragoes aflitos: navegagáo e travessia do Douro na Idade Média e no inicio da Época Moderna". Douro. Estudos & Documentos 2(4) (Porto, 1997): 77-118.

Enjalbert, Henri. "Comment naissent les grands crus: Bordeaux, Porto, Cognac". Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations 8(3) (Paris, 1953): 315-328.

Fernandes, Rui. Descrigáo do terreno em redor de Lamego duas léguas [1531-1532]. Edigáo crítica de Amándio Morais Barros. Lamego, Beira Douro, 2001.

Fonseca, Alvaro Baltasar Moreira da. As demarcagoes pombalinas no Douro vinhateiro. Vol. 2. Porto, Instituto do Vinho do Porto, 1950.

----- . O benefício e a sua distribuigáo na regiáo vinhateira do Douro. Régua, Casa do Douro, 1949.

Fonseca, Francisco Pereira Rebelo da. "Descrigáo económica do território que vulgarmente se chama Alto Douro". In: Memorias Económicas da Academia Real das Ciencias de Lisboa. Vol. 3. Lisboa, Academia Real das Ciencias de Lisboa, 1791: 36-72.

Macedo, Jorge Borges de. A situagáo económica no tempo de Pombal. 2a ed. Lisboa: Moraes Ed., 1982.

Oliveira, Aurélio de. "Vinhos de Cima-Douro na primeira metade do século XVII: a primeira grande questáo vinícola do Douro". Gaya 2. Vila Nova de Gaia, Cámara Municipal de Vila Nova de Gaia, 1984: 213-230.

Pereira, Gaspar Martins y Amándio Barros. "Wine Trade in the Early Modern Period: a Comparative Perspective from Porto". En: Celestino Pérez, Sebastián y Juan Blánquez Pérez (ed.). Patrimonio cultural de la vid y el vino / Vine and Wine Cultural Heritage. Madrid, UAM Ediciones, 2013: 195-209.

Tenreiro, A. Guerra. Douro, Esbogos para a sua História Económica. Conclusoes. Porto, Instituto do Vinho do Porto, 1944.

Unwin, Tim. Wine and the Vine. An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade. London/New York, Routledge, 1991.

Ventura, Margarida Garcez. "O vinho e o estatuto de vizinhanga de alguns abades do bispado do Porto, ou de como do facto económico se passa á história política". Douro. Estudos & Documentos 3(5) (Porto, 1998): 89-93.

Recibido: 01/12/2015 Aprobado: 23/01/2016

Revista RIVAR

es editada bajo licencia CREATIVE

COMMONS